Digital Gallery

Harm Reduction/Clean Needles

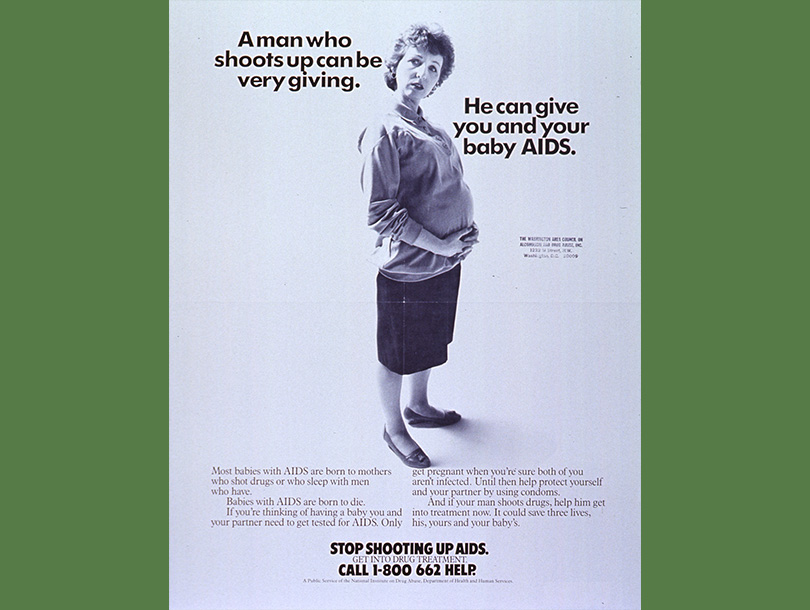

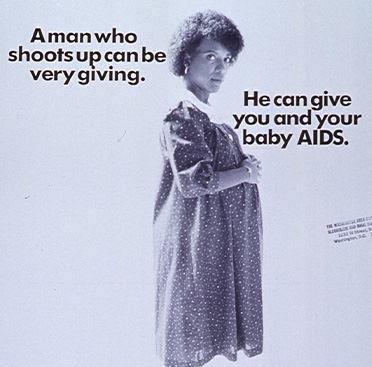

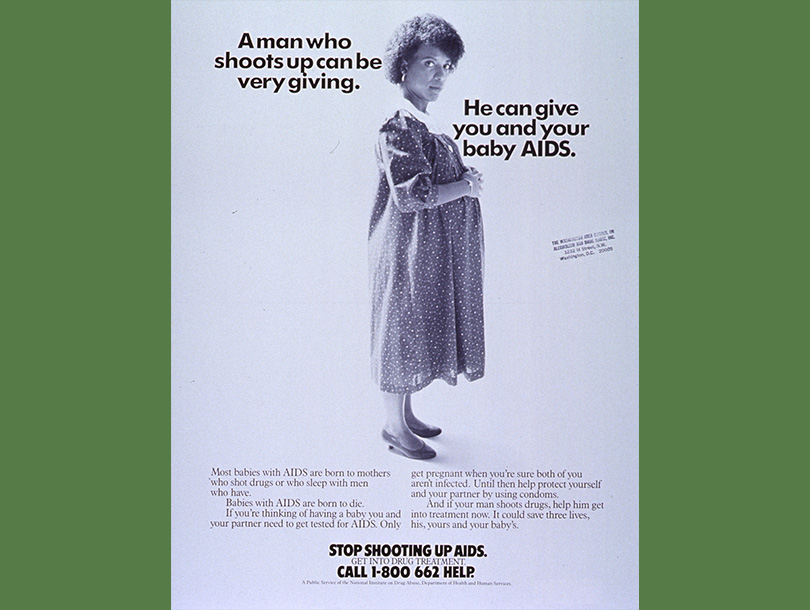

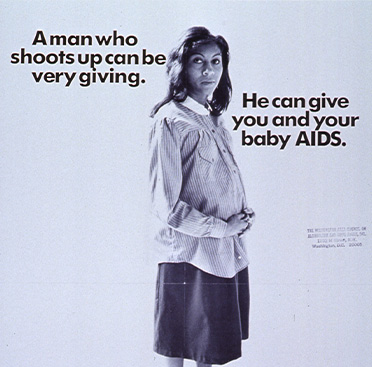

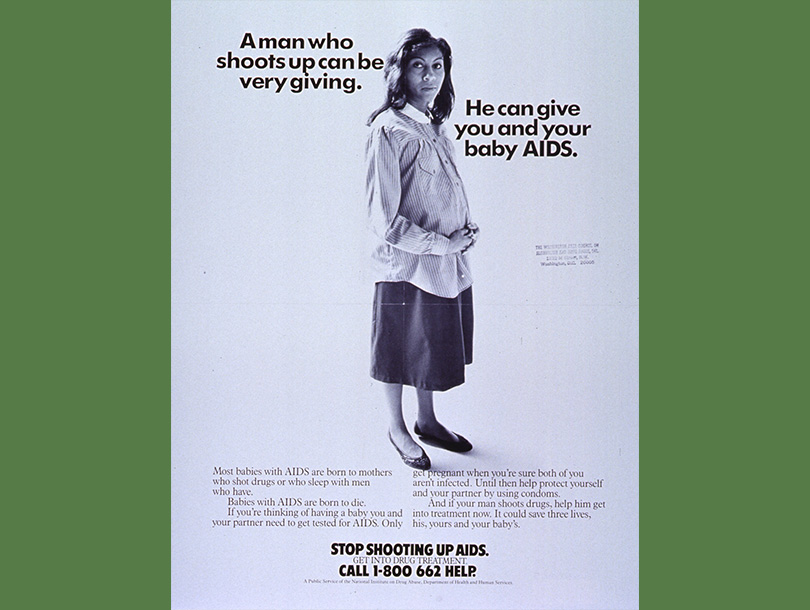

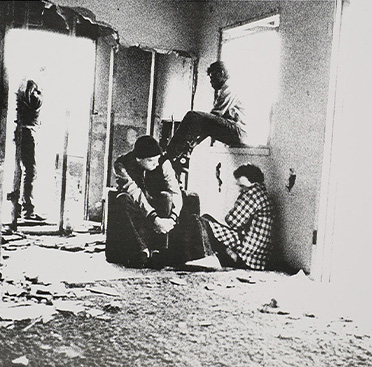

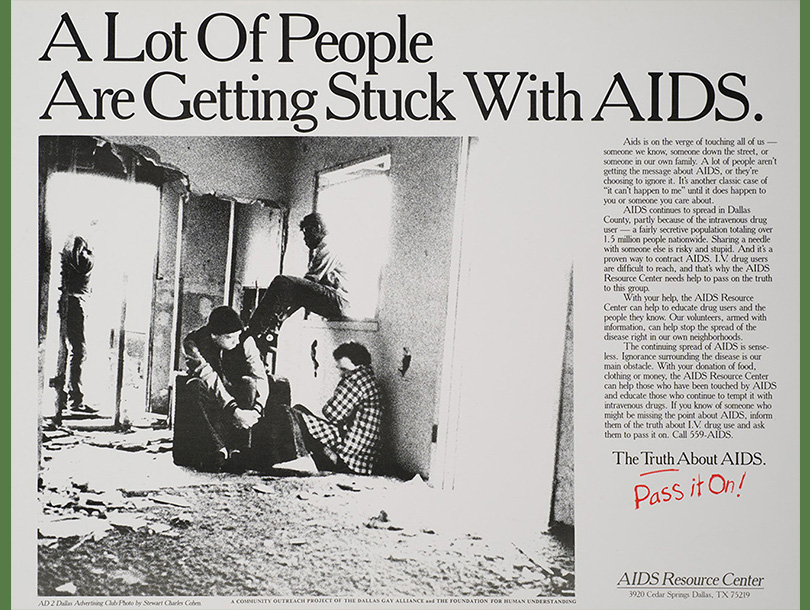

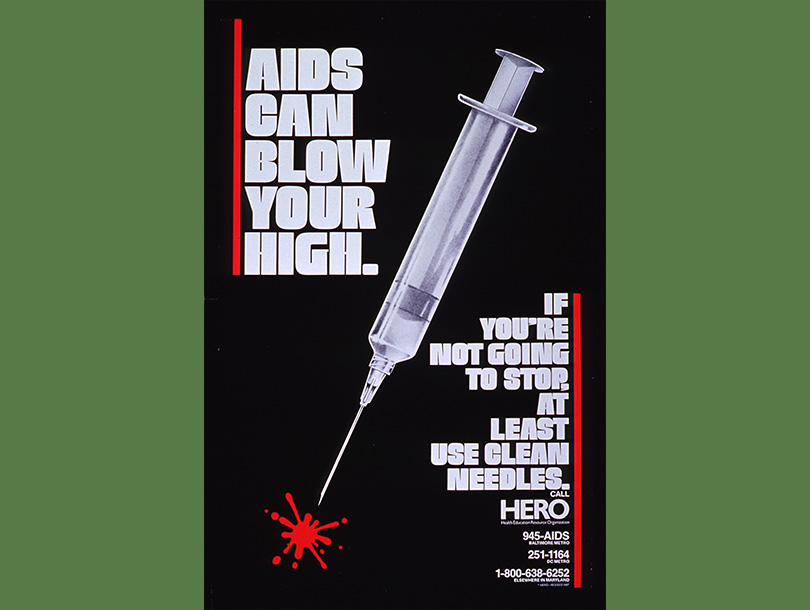

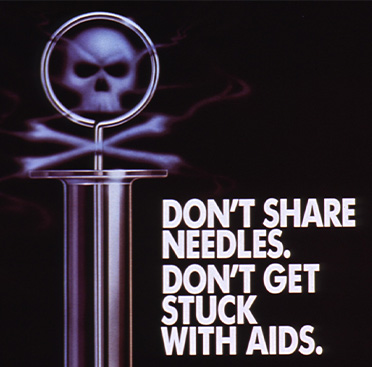

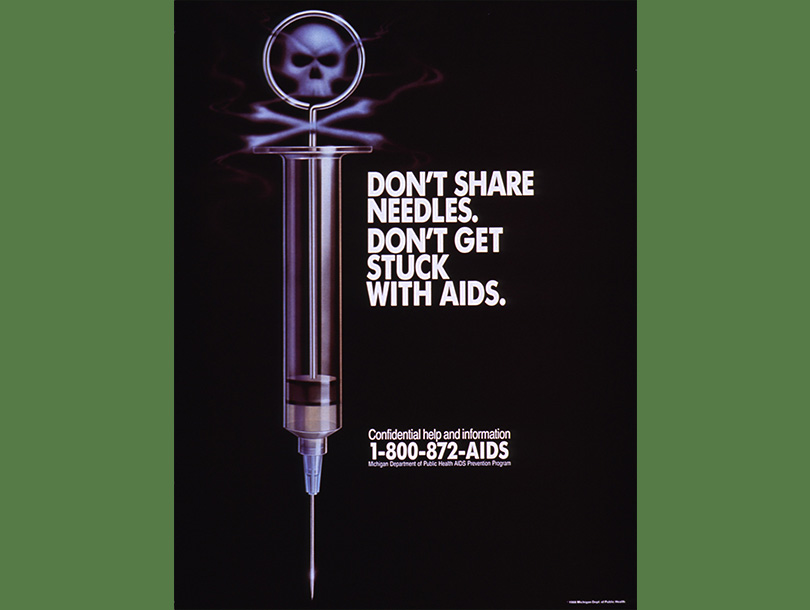

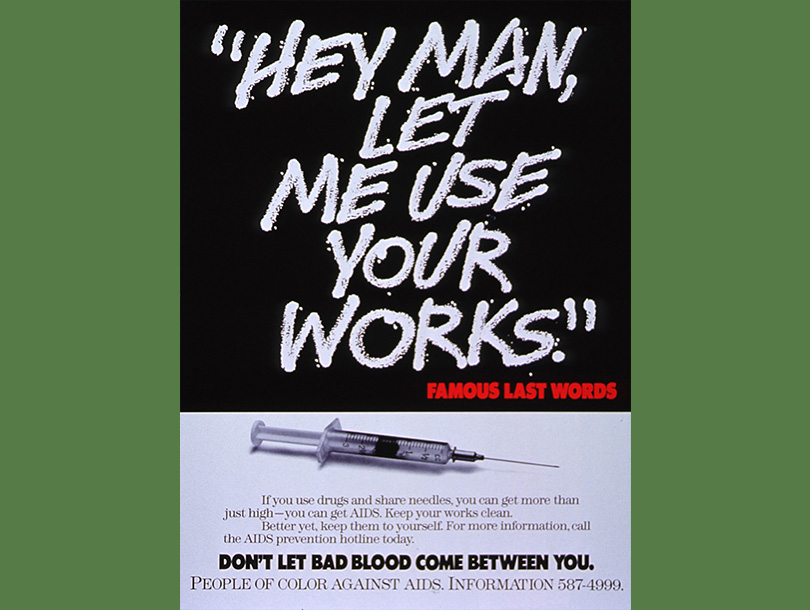

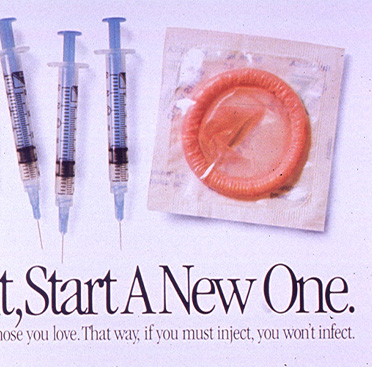

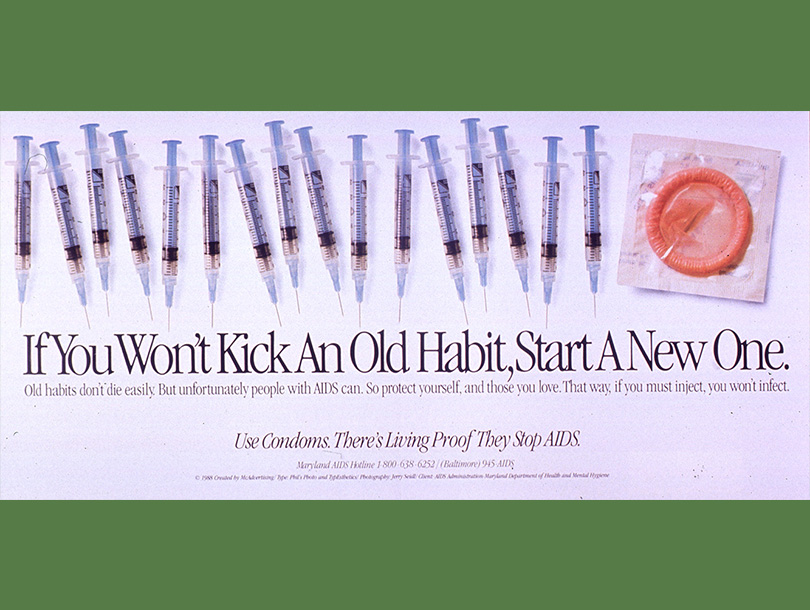

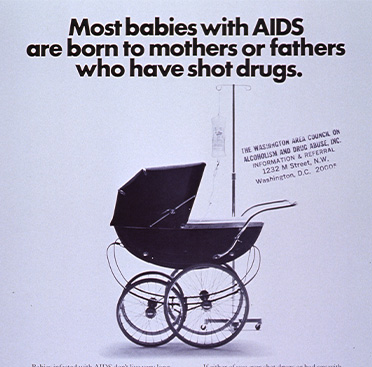

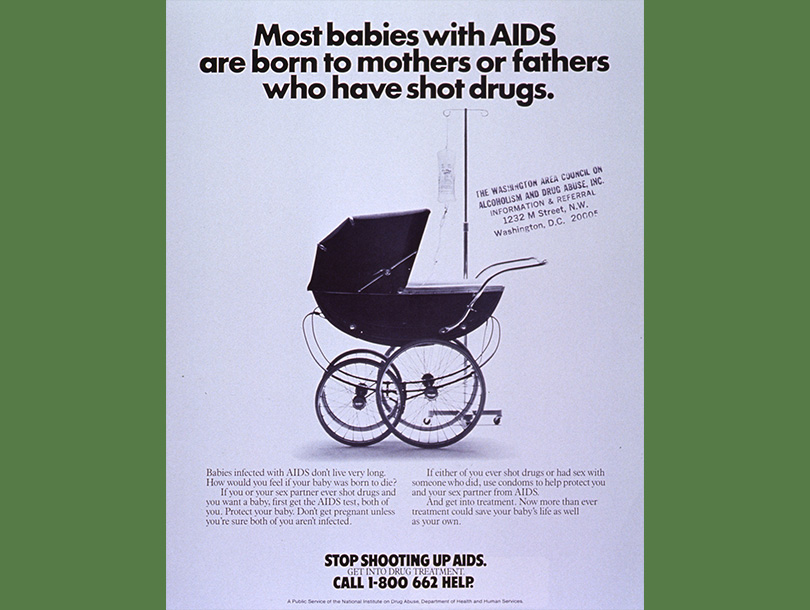

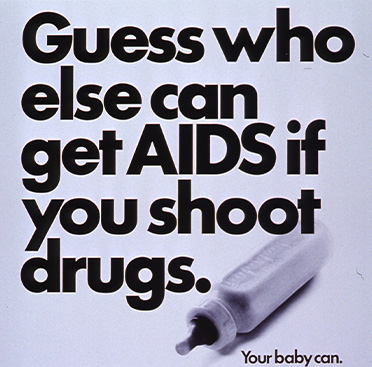

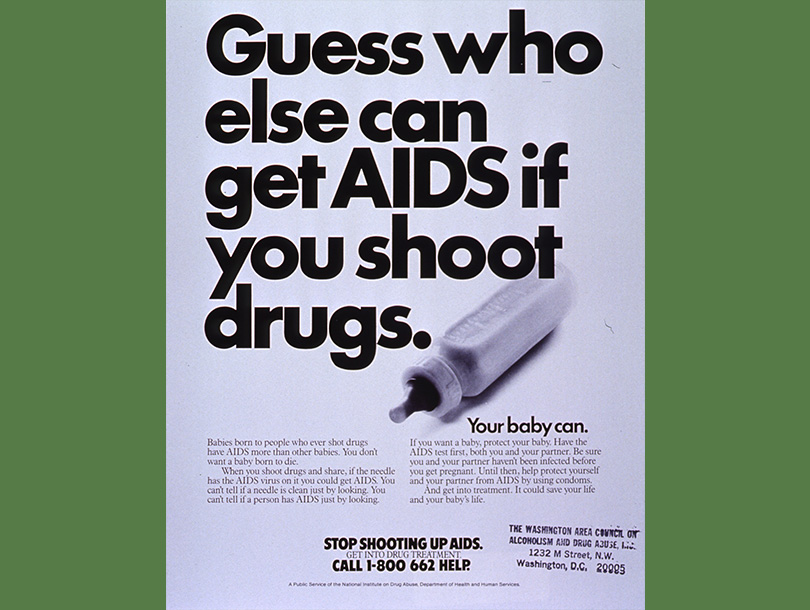

In the early 1980s, many believed that identity not behavior put people at risk for contracting AIDS. Known collectively as the 4 H’s: homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin users (representing all intravenous drug users), and Haitians, the four groups were considered vulnerable and blamed for spreading the disease. Intravenous drug users brought with them an all-too-familiar public health challenge. How do you inform, protect, and support a group that engages in behaviors deemed illegal and potentially considered wrong or sinful?

One answer, as illustrated in these public health campaigns, was harm reduction—the idea that if you could not stop people from using intravenous drugs, you could provide people with information about how to protect themselves while doing so. Using straightforward language, these campaigns spoke to needle users and the people who had sex with them.

The Minority AIDS Project

In 1985, four years into the national health crisis, African Americans and Latinos accounted for three times as many cases of AIDS as whites. To address the growing disparate epidemic and counter the myth that AIDS was a “gay white disease,” Archbishop Carl Bean and members of the Unity Fellowship Church founded the Minority AIDS Project (MAP) to support communities in southern Los Angeles. Their bold, bilingual campaigns stressed AIDS as a very serious, rapidly growing problem in communities of color and provided information on prevention and care for those with AIDS. MAP, working alongside two other community-based organizations—Blacks Educating Blacks About Sexual Health Issues (BEBASHI) and Black and White Men Together—became examples for future organizations focused on assisting African Americans and Latinos affected by HIV/AIDS.

View images in this themeNative People Respond to HIV/AIDS

Since 1987, the National Native American AIDS Prevention Center (NNAAPC) has offered programs and outreach to Native communities. The NNAAPC's Social Marketing Clearinghouse includes a variety of educational resources, including posters, which have been tailored to individual Native nations in many parts of the country. Many of the posters displayed here reflect the work of tribal governments and local community organizations as they strive to educate their citizens and non-Native neighbors about AIDS. Although not originally focused on HIV/AIDS prevention or awareness, staff at health clinics and support organizations frequently counseled individuals on pursuing safer, healthier behaviors and, in the process, became key participants in fighting the epidemic in Indian Country. The images here reflect an array of culturally— and oftentimes tribally-specific messages aimed at a broad, new audience that required help and information.

View images in this themeThe Whitman-Walker Clinic

Initially called the Gay Men’s VD Clinic upon its opening in 1973, the Whitman-Walker clinic was renamed in 1978, in honor of Walt Whitman, the famous American poet, who made his life with men, and Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, a feminist activist and medical doctor, who dressed exclusively in men’s clothes and was the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor for her service as a surgeon during the Civil War.

As early as 1983, the clinic staffed the first AIDS hotline in the city, and within two years, it opened multiple homes for people with AIDS. In addition, Whitman-Walker was at the forefront of designing and distributing safer-sex materials that targeted a range of audiences. Even as the clinic created campaigns to help all kinds of people, it never forgot to attend specifically to the needs of men who had sex with men.

View images in this theme“Please Be Safe” by the Northwest AIDS Foundation

In 1987, with funding from the U.S. Conference of Mayors, the Seattle-based Northwest AIDS Foundation launched the “Please Be Safe” campaign to help gay and bisexual men reimagine their sexual behaviors. Using a different creative visual strategy than the sexually charged imagery of some contemporaneous public health efforts, this campaign used road signs—a straightforward, familiar set of symbols—to discuss and advertise sexual safety. The “Please be Safe” or “Rules of the Road” campaign used road signs and compelling, straightforward, community-specific language to help gay men engage in safer sex. The “Sexual Safety Card” featured on many of the posters provided quick and accessible information on activities at every level of safety.

View images in this themeSouth Carolina AIDS Education Network (SCAEN)

In 1986, DiAna DiAna, an African American hairdresser with a salon in Columbia, South Carolina, took action when a local newspaper refused to run an advertisement for condoms. She began to use her salon as a space to engage customers in conversations about safer sex.

Later on DiAna met Bambi Sumpter (now Gaddist), a public health educator, at an AIDS workshop. The two women formed the South Carolina AIDS Education Network (SCAEN). The organization initiated a full-scale campaign to use popular culture to entice people to think about AIDS prevention. They wrote plays, and held Tupperware-style parties with prizes that could be used to make sex safe.

Emerging from this culture are a series of posters, by an unknown artist, that typify DiAna's approach to AIDS prevention: positioning the epidemic as a situation empowered community members could take on.

View images in this themeHarm Reduction/Clean Needles

In the early 1980s, many believed that identity not behavior put people at risk for contracting AIDS. Known collectively as the 4 H’s: homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin users (representing all intravenous drug users), and Haitians, the four groups were considered vulnerable and blamed for spreading the disease. Intravenous drug users brought with them an all-too-familiar public health challenge. How do you inform, protect, and support a group that engages in behaviors deemed illegal and potentially considered wrong or sinful?

One answer, as illustrated in these public health campaigns, was harm reduction—the idea that if you could not stop people from using intravenous drugs, you could provide people with information about how to protect themselves while doing so. Using straightforward language, these campaigns spoke to needle users and the people who had sex with them.

View images in this themePostcard Politics

By the mid-1980s, as the AIDS epidemic became a full-on crisis, AIDS activists turned to art and graphic design to illustrate and punctuate their responses to the disease and the resulting social crises. Soon artistic activism insisted that visual culture had tremendous power to affect behavioral and political change. Artists and activists plastered urban neighborhoods with posters featuring provocative images that forced some to confront their homophobia and others to reimagine what they could do to fight AIDS.

In addition to creating posters, artists reproduced those images as postcards. These small, portable, inexpensive items were visual reminders of how big the AIDS crisis had become. Displayed for the taking at bars, restaurants, neighborhood shops, and community centers, these postcards allowed activists to reach an even wider audience.

View images in this theme