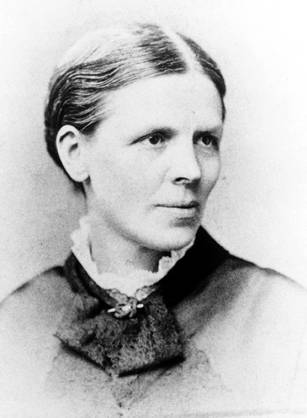

Biography: Dr. Emeline Horton Cleveland

Year: 1875

Achievement: Dr. Emeline Cleveland was one the first American women physicians to perform major gynecological and abdominal surgery.

Emeline Horton Cleveland entered medicine with strong religious convictions and a desire to minister to the suffering. From her earliest years, she dreamed of service as a foreign missionary, but instead went on to a brilliant career in medicine, becoming a highly respected physician and one of the first American women physicians to perform major gynecological and abdominal surgery. At a time when women's entry into the profession faced serious opposition, Dr. Cleveland was a striking example of women's capabilities.

Born in Ashford, Connecticut, in 1829, Emeline Horton was third in a family of nine children. When she was 2 years old, the family moved to a farm in Madison County, New York, where the children were educated at local schools and by private tutors. Determined to realize her dreams of becoming a missionary, she taught school for a number of years, saving her wages to pay for entry to Ohio's Oberlin College in 1850.

Her future husband and longtime friend, Giles Butler Cleveland, entered Oberlin's Theological Seminary around the same time and the pair began to plan their missionary career together. After graduating from Oberlin, Emeline Horton registered at the Female (later Woman's) Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1853. The couple married in 1854, a year before Emeline Horton Cleveland received her medical degree. Her husband's poor health stifled any plans to enter missionary service and Dr. Cleveland set up a private practice in Oneida Valley, New York, to support them both.

In the autumn of 1856, Dr. Cleveland was invited back to the Female Medical College to teach anatomy. The couple moved back to Philadelphia, where Giles Cleveland found work as a teacher. But another illness during the winter of 1857-1858 left him partially paralyzed, making Emeline Cleveland fully responsible for supporting the family. Cleveland remained at the Female Medical College until 1860.

Since Philadelphia hospitals refused to allow women medical students into wards or clinics at this time, it was difficult for them to receive instruction with patients. Dr. Ann Preston, a colleague of Cleveland's at the Medical College, along with several Quaker women who lived in the area, were firmly committed to both adequate training for female physicians and to a woman's right to be treated by a woman doctor. They were determined to establish their own hospital and offer Cleveland the post of chief resident. They set out to secure Cleveland the best available training and paid for her to study abroad. In August 1860, Cleveland went to Paris to study obstetrics and gynecological surgery. She earned a diploma and toured the lecture halls and hospitals of Paris and London, studying surgery and hospital administration.

In 1862, Dr. Cleveland took up the position of chief resident at the newly established Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia, established by Dr. Preston. During the next seven years, Dr. Cleveland developed some of the first training programs for nurses and nurses' aides in the United States. She also gave birth to a son, who would later follow her into a medical career. She continued teaching at the Female Medical College as well as running a private practice until 1878.

When Dr. Preston died in 1872, Dr. Cleveland succeeded her as dean of the Woman's Medical College, where she remained until ill health forced her to resign in 1874. In 1878, Cleveland was appointed gynecologist at Pennsylvania Hospital's Department for the Insane, becoming one of the country's first woman physicians to be hired by a major public medical institution. That same year, she died of tuberculosis at age forty-nine. Described as a woman of great charm and intellect, Cleveland helped to establish the legitimacy of women's surgical roles in the face of immense opposition. She also did much for the development of the Woman's Medical College at a critical stage in its development. Illustrating her commitment to this institution and to her colleagues there, her final request was to be buried beside her friend and fellow physician, Dr. Preston.