Exhibition Gallery

Exhibition Gallery

Portrait Gallery

Celebrating America's Women Physicians

Women have always been healers. As mothers and grandmothers, women have always nursed the sick in their homes. As midwives, wise women, and curanderas, women have always cared for people in their communities. Yet, when medicine became established as a formal profession in Europe and America, women were shut out.

Women waged a long battle to gain access to medical education and hospital training. Since then, they have overcome prejudices and discrimination to create and broaden opportunities within the profession. Gradually, women from diverse backgrounds have carved out successful careers in every aspect of medicine.

Changing the Face of Medicine introduces some of the many extraordinary and fascinating women who have studied and practiced medicine.

This 2003 exhibition honors the lives and achievements in medicine. Women physicians have excelled in many diverse medical careers. Some have advanced the field of surgery by developing innovative procedures. Some have won the Nobel prize. Others have brought new attention to the health and well-being of children. Many have reemphasized the art of healing and the roles of culture and spirituality in medicine.

Celebrating America's Women Physicians

Women have always been healers. As mothers and grandmothers, women have always nursed the sick in their homes. As midwives, wise women, and curanderas, women have always cared for people in their communities. Yet, when medicine became established as a formal profession in Europe and America, women were shut out.

Women waged a long battle to gain access to medical education and hospital training. Since then, they have overcome prejudices and discrimination to create and broaden opportunities within the profession. Gradually, women from diverse backgrounds have carved out successful careers in every aspect of medicine.

Changing the Face of Medicine introduces some of the many extraordinary and fascinating women who have studied and practiced medicine.

This 2003 exhibition honors the lives and achievements in medicine. Women physicians have excelled in many diverse medical careers. Some have advanced the field of surgery by developing innovative procedures. Some have won the Nobel prize. Others have brought new attention to the health and well-being of children. Many have reemphasized the art of healing and the roles of culture and spirituality in medicine.

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Tenley E. Albright

Dr. Tenley Albright became the first American woman to win an Olympic gold medal in figure skating before breaking boundaries in the field of surgery.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Albright.

-

ReadBiography

-

Transcript

Dr. Tenley E. Albright. In 1956 the Olympics was in Cortina, Italy, in the mountains, and we skated outdoors. It’s sort of a hyper-sensation, hyper-perception, you’re able to think of many, many things at once. I was aware of so many things. Of the people in the audience, about where I was standing, where the sun was crossing the ice, where I’d take off in the dark and land in the sun, what the mountains looked like, what the moment was. And so when you’re there in this magical world of the operating room, with a patient and with a team, and you’re dealing with something, you never know totally what you’re going to find until you’re there. It’s sort of like that multidimensional thinking that I was aware of on the ice, where everything comes into your head at once. You have to be focused, but you also have to be conscious of all sorts of things, for the benefit of having the surgery turn out the way you want it to. Doing whatever I can to make a difference in one life, or part of one life, that motivates me to want to do that more. And anything I can do to make a bigger change—whether it’s helping to change attitudes or ways of doing things or just to encourage all of us to have sort of a sense of openness— that’s really what I’d like to do.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Mary Ellen Avery

Dr. Mary Ellen Avery helped discover the cause of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in premature babies. Additionally, she trained and advocated for young physicians in a long career in academic medicine.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Avery.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Mary Ellen Avery. My next door neighbor was professor of pediatrics at Woman’s Medical College in Pennsylvania—Dr. Emily Bacon— and she kindly reached out to me in many ways, and I saw her life as more exciting and meaningful than most of the women I knew—who were my mothers friends, for example, who were busy doing good works, raising children (and I admired them greatly), but I still thought Emily Bacon had something going for her in terms of reaching out to all children. But mainly, she reached out to me, and I’m eternally grateful. So I applied to Johns Hopkins and Harvard. And Harvard didn’t take women at that time but I didn’t know it, and Johns Hopkins did. In fact they had to. They were founded by a woman who had insisted that they wouldn’t get the money to build the school if they didn’t take women on an equal basis with men, and I thought, “Hey, that neutralizes the problem in one dimension,” and Emily Bacon graduated from Johns Hopkins. So there was no question where I was going to go to medical school. I received the National Medal of Science in 1991. It is America’s highest award for all of science. And so there had been very few pediatricians if any, that had ever been given the medal. They’ve given maybe ten or fifteen a year. It’s presented by the President of the United States to the nominee. This has been very, very rewarding. And I feel that I am a citizen of this one world and that I can resonate with people with a lot in common—it’s called science and science methods. And I am so saturated and pleased to share it with anybody who will listen, and that makes for a very fulfilling life.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Nancy E. Jasso

Dr. Nancy Jasso is one of the founding physicians of a laser tattoo–removal project for the San Fernando Valley Violence Prevention Coalition, which serves people who leave gangs.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Jasso.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Nancy E. Jasso. For many people with tattoos, it’s actually life threatening to them to walk the streets. If they happen to have the wrong tattoo in the wrong neighborhood, then that means they might get shot, and they may not make it to the next day. In addition, it’s very difficult for them to secure employment when they have tattoos. There’s lots of value judgments about having tattoos, lots of concern for safety, and what their affiliations might be with either gangs or drugs, and so many people cannot get employed if they have tattoos. I have a lot of respect for the patients in the Tattoo Clinic. These are patients who are really trying to change their lives, and change is hard. And yet they’ve been courageous enough to actually try to put their life on a different track. So I figure anything that I can do to be helpful to them, I'm very willing to do. Well, I think fundamentally, being a physician is really an honor. It’s really a privilege to walk that path with another human being. People come in because they’re suffering and they’re in need of help, and I have the privilege of being there to try to assist them. And I really do see it like a partnership. It’s not really a one-way street. I certainly have my bag of tricks and all of the years of study under my belt, but it really takes kind of the two of us working together to really come up with something that’s going to help them.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Vivian W. Pinn

Dr. Vivian Pinn served as the first full–time director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additionally, she was the first African American woman to chair an academic pathology department in the United States, at Howard University College of Medicine.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Pinn.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Vivian W. Pinn. Having the opportunity to come be the first permanent Director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) represented not only a career change for me, but also a very, very exciting opportunity that I have tried to make the best of in every way that I could. We didn’t really have a good focus on what is now called Women’s Health up until about the time this office was established. The office at NIH is really the first office established within the Federal Government to focus on women’s health issues. It was established to make sure that women are included in clinical studies funded by the NIH—in other words, included in research—and to make sure that research is addressing the health of women in studies. I always wanted to be a physician and I always thought that was what I wanted to do. But my sophomore year in college, my mother developed a bad pain in her back. And the doctors thought it was arthritis. And I can remember going with her to the doctor and having him say, “Francina, if you just wore those oxfords I gave you and stood up straight and did those exercises, you wouldn’t have that pain.” But it turned out what he had missed, was that she had a bone tumor. I interrupted my career and stayed home with my mother and took care of her 24 hours a day until she died, which was in February of 1961. Then I went back to school with even more resolve that I wanted to be a physician, and I wanted to be the kind of physician who paid attention to my patients, and didn’t dismiss my patient’s complaints—something that has really carried through and I think has been central to my way of thinking and approaching women’s health in this portion of my career.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Esther M. Sternberg

Dr. Esther Sternberg is internationally recognized for her groundbreaking work on the mind–body connection in illness and healing.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Sternberg.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Esther M. Sternberg. It’s really hard to say “Okay, I’ve made a discovery, and I know I’ve helped thousands of people, or millions of people.” It’s when you see the one patient that really has benefited from that discovery that you really know that you’ve helped. When the family member can come up to you and say, “Thank you, you helped save my mother.” That really makes a difference. And I think that’s what motivated me from the beginning when I started seeing patients on a one-on-one basis, when you know that you’ve saved a life. And then if you make a discovery in the lab, in a rat, that you know can be applied to saving many lives — that really is tremendously rewarding. For so many thousands of years, the popular culture believed that stress could make you sick, that believing could make you well. And people believe what they feel. But scientists need evidence. And there really wasn’t any good, solid scientific evidence to prove these connections. Nor was there a good way to measure them. And scientists only believe what they can actually measure. Once scientists and physicians believed that there was a connection between the brain and the immune system, you could then take it to the next step: that maybe there is a connection between emotions and disease. Between negative emotions and disease, and positive emotions and health. And we can then say, okay, maybe these alternative approaches that have been used for thousands of years — approaches like meditation, prayer, music, sleep, dreams — all of these approaches that we really know in our heart of hearts really work to maintain health... Maybe there is a scientific basis for it.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Donna M. Christian-Christensen

Dr. Donna Christian–Christensen is the first woman physician to serve in Congress and the first woman delegate for the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Christian–Christensen.

-

ReadBiography

-

Transcript

Dr. Donna M. Christian-Christensen. If you had asked me when I was graduating from George Washington in 1970 if I would be here doing this, I would have said no. And if you had asked me in 1996, when I got elected, if I would be in a position to influence national health issues, or international health issues, I would have told you, “Oh, no, that wasn’t possible,” but today it is. And it’s really an honor and a privilege, and a responsibility, to be able to do that. Starting coalitions is a lot of work. You end up doing all of it yourself. So I thought, well let me see, maybe I could join an organization that already exists that I could work through, and do some of the same kinds of things. And so I ended up joining the Democratic Party. And I was the first female delegate from the U.S. Virgin Islands— the first female delegate from any of the territories as a matter of fact—and then the first female physician ever to serve in the Congress. I think it’s really important for young people of color to see people of their own racial or ethnic background in positions like mine—not only on the political front, but also as a health care provider—so that they will know that yes, it’s possible for them. Because sometimes in their day-to-day environment it may not seem that way. So I think it’s really encouraging for them to see us and to interact with us.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Nancy L. Snyderman

Dr. Nancy Snyderman had a decades’ long career in broadcast medical journalism, serving as a correspondent for ABC television’s Good Morning America for 15 years.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Snyderman.

-

ReadBiography

-

Transcript

Dr. Nancy L. Snyderman. No matter where I have been at any stage of my life I’ve always been a doctor first, and everything else second— except maybe being a mom. But I’ve never seen myself as a doctor correspondent who just happens to do surgery. I’ve always defined myself as a practicing surgeon who happens to also have a second career in broadcast journalism. I started combining my love of television with my love of medicine. And the two weaved themselves together quite well. The passion in broadcasting is different. The best stuff I’ve done has been in the worst places on earth. Kosovo. Mogadishu. Bosnia. The Persian Gulf. Afghanistan. Pakistan. I think when you get a chance to look around you and see the world suffering, and you’ve reached down deep inside yourself and tried to explain that to people who may never have the good fortune to travel, in the same way, that’s where I get my passion. And if you look at the people entering medicine today, they’re as bright as people have ever been. The youngsters entering medicine today will enter on their own terms. And they’ll make medicine what they want it to be. But I want young people—particularly young girls—to discover the thrill of science, and biology, and physics, and how it all works. And for my two girls, every time we can draw science or biology into life, we do it. Medicine’s filled with a lot of kicks. And the other great thing is, it’s this blank canvas. You want to go into medicine? You get to do anything you want to do. Become a neuropsychiatrist, become a physicist, become a neurosurgeon, be in the lab, see patients, work part-time, full-time, have kids, don’t have kids— you get to do it on your own terms. It’s great. And you can always put food on the table.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Setting Their Sights

Before women could build careers as physicians, they had to fight even to be allowed to attend medical school. After proving that they were as capable as men, they went on to campaign for additional professional training and other career opportunities.

As part of the wider movement for women’s rights during the mid–1800s, women campaigned for admission to medical schools and the opportunity to learn and work alongside men in the professions. Such rights came slowly. Even after qualifying as physicians, women were often excluded from employment in medical schools, hospitals, clinics, and laboratories.

To provide access to these opportunities, many among the first generation of women physicians established women’s medical colleges or hospitals for women and children.

Persistence, ingenuity, and ability enabled women to advance into all areas of science and medicine. Courageously, they worked long and hard to succeed even where they were most unwelcome, such as in surgery and scientific research.

Setting Their Sights

Opening Doors

The first women to complete medical training and launch careers confronted daunting professional and social restrictions. To establish their rightful place as physicians and to expand opportunities for other women in medicine, they devised many strategies, establishing their own hospitals, schools, and professional societies. They excelled in their chosen fields of medical practice and scientific research—often while campaigning for political change and managing the administrative responsibilities and financial affairs of educational and medical institutions.

By succeeding in work considered “unsuitable” for women, these leaders overturned prevailing assumptions about the supposedly lesser intellectual abilities of women and the traditional responsibilities of wives and mothers.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 0

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

When she graduated from New York’s Geneva Medical College, in 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in America to earn the M.D. degree. She supported medical education for women and helped many other women’s careers. By establishing the New York Infirmary in 1857, she offered a practical solution to one of the problems facing women who were rejected from internships elsewhere but determined to expand their skills as physicians. She also published several important books on the issue of women in medicine, including Medicine as a Profession For Women in 1860 and Address on the Medical Education of Women in 1864.

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

-

ReadBiography

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Mary Corinna Putnam Jacobi

Mary Putnam Jacobi was an esteemed medical practitioner and teacher, a harsh critic of the exclusion of women from the professions, and a social reformer dedicated to the expansion of educational opportunities for women. She was also a well–respected scientist, supporting her arguments for the rights of women with the scientific proofs of her time.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC–USZ62–61783

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

-

Gathering Data

Before the sphygmograph was developed, physicians assessed pulse strength by placing their fingers on a patient’s wrist and feeling for arterial resistance. The sphygmograph offered a more consistent method to assess, compare, and present information about the strength of the pulse. Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi used the device in her research.

National Library of Medicine

-

ReadBiography

-

EnlargeImage

-

Transcript

Gathering Data Before the sphygmograph was developed, physicians assessed pulse strength by placing their fingers on a patient’s wrist and feeling for arterial resistance. The sphygmograph offered a more consistent method to assess, compare, and present information about the strength of the pulse. Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi used the device in her research. Screw recording. Stylus. smoked paper transporter. smoked paper. pressure sensor. ivory rests. pressure dial. clockwork mechanism.

-

Copy Link

Copied

-

-

Mahomed sphygmograph, ca. 1880

A number of sphygmographs (instruments to measure and record the force of the pulse) were developed during the 19th century. The one shown here was designed during the 1870s by medical student F. A. Mahomed. One end of a metal stylus was strapped to the subject’s wrist, allowing the pressure of the pulse through an artery to move the other end of the stylus, tracing a record across sliding, smoke–blackened paper.

M. Donald Blaufox, M.D., Ph.D.

-

ReadBiography

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

-

Dr. Jacobi's Sphygmograph

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 0

Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer

Emily Dunning Barringer harnessed the benefits of a good education and gained the mentorship of a leading woman physician of her era, Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi, to overcome barriers in her own career and to make it possible for other women physicians to serve their country during World War II. After first being denied an appointment at New York’s Gouverneur Hospital, she was later allowed to take up the position and became the hospital’s first woman medical resident and ambulance physician. During World War II, Barringer lobbied Congress to allow women physicians to serve as commissioned officers in the Army Medical Reserve Corps, and in 1943 the passing of the Sparkman Act granted women the right to receive commissions in the army, navy, and Public Health Service.

New York Times Archive

-

ReadBiography

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 0

Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer

Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer became the first woman medical resident and ambulance physician in New York. She also lobbied Congress to allow women physicians to receive commissions in the Armed Forces and the Public Health Service.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dunning Barringer.

-

ReadBiography

-

Transcript

Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer became the first woman to ride with ambulance crews as an emergency physician, in New York City, working from a horse-drawn wagon in the neighborhoods of the Lower East Side. Originally, Emily Dunning thought she would become a nurse. It was Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi who recommended Cornell University’s medical preparatory course for her education instead. Dr. Jacobi believed Emily Dunning would choose to become a doctor. In 1897 she enrolled at the College of Medicine of the New York Infirmary. The day after she completed her residency, in 1904, she married Dr. Benjamin Barringer. Quickly, she became frustrated that his prospects were so much better than hers. She said, “He could count on a splendid training in one of the big general hospitals... with post-graduate work abroad, in whatever line he elected... And I? What did I see ahead?” Her opportunities seemed greatly limited. Again, Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi advised Dr. Barringer, urging her to take the competitive internship exams held by New York’s large area hospitals even though women had never been allowed to compete. Together, the two women pressured several hospitals to open their internships to women. Dr. Barringer became the first woman medical resident at Gouverneur Hospital in New York City. Her male colleagues harassed her assigning her difficult schedules for on-call and ward duties. She continued with her work, despite these difficult circumstances and was widely reported in the local papers as something of a novelty as a woman ambulance physician. During World War II, Dr. Barringer made headlines again, lobbying Congress for military commissions for women physicians. While women could serve as contract surgeons in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, they were not commissioned employees, and so were not given the same benefits as men. In 1943, the Sparkman Act was signed into law, allowing women the same benefits as men in the Army and Navy. Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer created a legacy of helping women achieve equal status, in the medical profession, and in the U.S. military; Opportunities passed on to the generations to come.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 0

Dr. Marie E. Zakrzewska

In 1862, Marie Zakrzewska, M.D., opened doors to women physicians who were excluded from clinical training opportunities at male–run hospitals, by establishing the first hospital in Boston—and the second hospital in America—run by women, the New England Hospital for Women and Children.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

-

ReadBiography

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 6 of 0

Dr. Marie E. Zakrzewska

Dr. Marie Zakrzewska founded the New England Hospital for Women and Children, the second hospital in the United States to be run by women physicians and surgeons.

Click on the video play button to watch a video Dr. Zakrzewska.

-

ReadBiography

-

Transcript

Dr. Marie E. Zakrewska In 1862, Dr. Marie Zakrzewska opened her own hospital, The New England Hospital for Women and Children. It was the first hospital in Boston, and only the second in America to be run by women physicians. Dr. Zakrzewska had been part of the first generation of women physicians in America. Barred from working in existing hospitals and excluded from teaching jobs at medical schools, some of these women went on to found dispensaries, hospitals, and schools to train women students and employ women physicians. Marie Zakrzewska was born in Berlin, the daughter of a midwife. As a young woman, she accompanied her mother on her rounds. She trained at the Royal Charité Hospital, and in 1852 become a midwife. When her promotion to Head Midwife not long after she had finished her training was met with disapproval from some of the faculty, she left to study medicine in the United States. Although opportunities in America were also limited, Marie Zakrzewska was aided by Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to graduate from medical school in America. With Dr. Blackwell’s help, she enrolled at Cleveland Western Reserve College, traditionally, an all-male medical school. Marie Zakrzewska was one of only six women admitted to the school in the 1850s. She graduated with her M.D. in 1856. Dr. Blackwell and her sister Emily became an inspiration to Dr. Zakrzewska by planning to found a small hospital where women physicians could work and learn. Dr. Zakrzewska joined their effort, and the New York Infirmary for Women and Children opened in 1857. She served as resident physician at the hospital for two years. She moved to Boston to accept the position of Professor of Obstetrics at the New England Female Medical College. Her students, encountering the same obstacles as other women physicians, found it difficult to get work after graduation. Dr. Zakrzewska also disagreed with the founder of the New England Female Medical College over the school’s curriculum. She had proposed courses in dissection and microscopy to enhance the training of students and keep up with the developing field of scientific medicine. But the director intended to limit women physicians to a lower educational level. Three years later, she resigned, to open her own hospital. The New England Hospital for Women and Children flourished under Dr. Zakrzewska’s direction. There, women physicians who were excluded from the majority of hospitals, could acquire clinical experience. She believed that women physicians must have the same training and base of scientific knowledge as their male counterparts to achieve the same levels of research and standards of practice.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 7 of 0

Dr. Ann Preston

As the first woman to be made dean of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP), Ann Preston campaigned for her students to be admitted to clinical lectures at the Philadelphia Hospital, and the Pennsylvania Hospital. Despite the hostility of the all–male student groups, she was determined to negotiate the best educational opportunities for the students of WMCP.

National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B030140

-

ReadBiography

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 8 of 0

Dr. Ann Preston

Dr. Ann Preston was the first woman dean of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and advocated for women students to receive medical education.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Preston.

-

ReadBiography

-

Transcript

Dr. Ann Preston In 1869, Dr. Ann Preston, the first woman Dean of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, campaigned for the right for her students to attend lectures at all-male institutions. When they were first granted admittance, women medical students attending a clinic were greeted by the male students with hisses and paper wads. Dr. Preston refused to be deterred, and successfully argued for the fair treatment and equal skill of her students. She was born a Quaker in 1813, and attended Quaker schools in Pennsylvania. From an early age, she campaigned for social reform. She wrote petitions and lectures for the Clarkson Anti-Slavery Society and joined the temperance movement. Wanting to educate women about their own bodies, she began teaching physiology and hygiene to all-female classes. In 1847, Ann Preston applied to four medical colleges in Philadelphia. But her applications, like those from all other women, were rejected. To provide opportunities for women to study medicine, a group of Quakers founded the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Ann Preston enrolled in the first class. She graduated in 1851, at the age of 38. She stayed on at the school, and in two years was appointed professor of physiology and hygiene. Public and professional attitudes toward women physicians remained negative, for the most part. Eight years after the medical school was established, the Philadelphia Medical Society spoke out against it, effectively barring women students from educational clinics and medical societies in the city. Undeterred, Dr. Ann Preston organized a board of wealthy supporters to fund and run a woman’s hospital, where her students could gain clinical experience. The hospital opened in 1861. Two years later, Dr. Preston established a School of Nursing. In 1865, Dr. Ann Preston became the first woman Dean of the Woman’s Medical College. Committed to expanding her students’ educational opportunities, Dr. Preston negotiated and won the right for them to attend general clinics at the Blockley Hospital in Philadelphia. In 1869, she made a similar arrangement with the Pennsylvania Hospital. There, the women endured harassment from the male students. As one student later recalled, “We were allowed to enter by way of the back stairs, and were greeted by the male students with hisses and paper wads, and frequently during the clinic were treated to more of the same... The Professor of Surgery came in and bowed to the men only...” Dr. Ann Preston publicly criticized the response of the men and the attitudes behind it, arguing that women students could easily keep up with the men but that the men refused to welcome their equally capable women colleagues. Thanks to Dr. Preston and her students, women studying alongside men gradually became a more frequent sight in the medical clinics and colleges of the late 1800s.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 9 of 0

Dr. Sarah Reed Adamson Dolley

Sarah Adamson Dolley of Rochester, New York, was the first woman physician to complete a hospital internship. She was a founder of one of the first general women’s medical societies, the Practitioners’ Society of Rochester, New York, and the Provident Dispensary for Women and Children (an outpatient clinic for the working poor) established by the society. She was also the first president of the Women’s Medical Society of New York State.

Edward G. Miner Library, Rochester New York

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 10 of 0

Dr. Sarah Reed Adamson Dolley

Dr. Sarah Adamson Dolley was the third woman medical graduate in the United States and the first woman to complete a hospital internship.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dolley.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Sarah Read Dolley Sarah Read Adamson was born in 1829 and became the third woman in America to earn an M.D. degree. Her family were Quakers living in Schuykill Meeting, Chester County, Pennsylvania. She was educated at The Friends’ School in Philadelphia. Sarah Adamson became interested in medicine when her teacher, Graceanna Lewis, gave her a physiology book to study at home. Her uncle, Hiram Corson, was a physician, and she had also read an anatomical book from his library. He agreed to tutor her, and took her on as an apprentice. This experience prepared her to study at the newly-opened Central Medical College in Rochester, New York, where she graduated from in 1851. Though a few women had broken through barriers to receive a medical education, no woman had ever completed a hospital internship. Dr. Adamson’s uncle again supported her, sponsoring her application for an internship at Blockley Hospital in Philadelphia. She became the first woman intern in America. In 1852, she married Dr. Lester Clinton Dolley, a professor of anatomy and surgery at Central Medical College. Together they traveled to Europe to gain further medical training, attending clinics in Paris, Prague, and Vienna. Upon their return, they set up a medical practice in Rochester, where they worked together until his death in 1872. For the next year, Dr. Sarah Dolley served as Professor of Obstetrics at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, but soon returned to Rochester to re-establish her practice. Women were still barred from working in most hospitals. Knowing how critical the knowledge and experience she had gained through her internship was, Dr. Dolley worked to open more hospital positions to women. In 1887, she helped a group of women open their own dispensary, an outpatient clinic for the working poor. She also helped found one of the first general women’s medical societies: The Practitioners’ Society of Rochester, which later became the Blackwell Society. On her seventy-eighth birthday, Dr. Sarah Adamson Dolley led the Blackwell Society in launching the Women’s Medical Society of the State of New York. She was given the honor of being its first president.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 11 of 0

Dr. Mary Amanda Dixon Jones

Dr. Mary Dixon Jones became a world–renowned surgeon for her treatment of diseases of the female reproductive system, in a time when few women physicians were able to build a career in the specialty. She is credited as the first person in America to propose and perform a full hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) for the treatment of uterine myoma (a tumor of muscle tissue). She trained with Mary Putnam Jacobi in New York and is considered one of the leading women scientists of the late nineteenth century.

Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine Library, copy by RD Rubic

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 12 of 0

Dr. Mary Amanda Dixon Jones

Dr. Mary Amanda Dixon Jones was a renowned surgeon credited as the first person to propose and perform a full hysterectomy to treat a tumor in uterine muscle tissue.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dixon Jones.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Mary Amanda Dixon Jones In 1888, Dr. Mary Dixon Jones performed a hysterectomy, removing a seventeen-pound tumor from her patient’s uterus. It was the first operation of its kind performed in America. Mary Dixon began her career as an apprentice to two leading male physicians. In 1854, she married a lawyer, John Quincy Adams Jones. They moved west to Illinois and Wisconsin, and had three children. In 1862, ten years after she had first begun studying medicine as an apprentice, Dixon Jones left to study at the Hygeio-Therapeutic Medical College in New York. After graduation, she moved to Brooklyn to start a private practice. Dr. Dixon Jones focused on obstetrical and gynecological surgery, a specialty that was developing rapidly at the time. She read about newly developed, innovative operations described in medical literature. She heard about new techniques taught in medical schools. But some of her patients had complicated and distressing gynecological problems that she was unsure how to treat. So, after ten years of successful private practice, she went back to school, enrolling at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. She also studied with Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi, to discover more about the latest in pathology and clinical diagnosis. After her graduation in 1875, she returned to private practice. For nine years, she also worked at the Woman’s Hospital of Brooklyn. Dr. Dixon Jones’ surgical skills and her use of innovative procedures earned her an impressive reputation and a successful practice. In 1888, she described her precedent-setting hysterectomy surgery in The New York Medical Journal, noting that within fifteen days of the surgery, the patient was almost fully recovered. In 1895, a Brooklyn newspaper slandered her surgical work. Dr. Dixon Jones sued for libel, but lost the case. As a result, her practice dwindled and she was forced to retire, so she turned to research. She studied diseases of the reproductive system and investigated the connections between surgical specimens under the microscope and many of the diseases she had treated. She was one of the few gynecological surgeons of her time to take up the laboratory study of specimens.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Setting Their Sights

Challenging Racial Barriers

The first women of color who gained access to medical school confronted financial hardships, discrimination against women, and racism. For generations, their families had been enslaved or oppressed. They had been denied the means of making a living and access to decent medical care. Even to begin training, these women often had to work their way through medical school or seek funding from supporters of women’s and minorities’ rights.

Once they became doctors, these women played an important role in bringing better standards of care to their own communities and served as role models for other women.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 0

Dr. Matilda Arabella Evans

Matilda Arabella Evans, who graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) in 1897, was the first African-American woman licensed to practice medicine in South Carolina. Evans’s survey of black school children’s health in Columbia, South Carolina, served as the basis for a permanent examination program within the South Carolina public school system. She also founded the Columbia Clinic Association, which provided health services and health education to families. She extended the program when she established the Negro Health Association of South Carolina, to educate families throughout the state on proper health care procedures.

South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

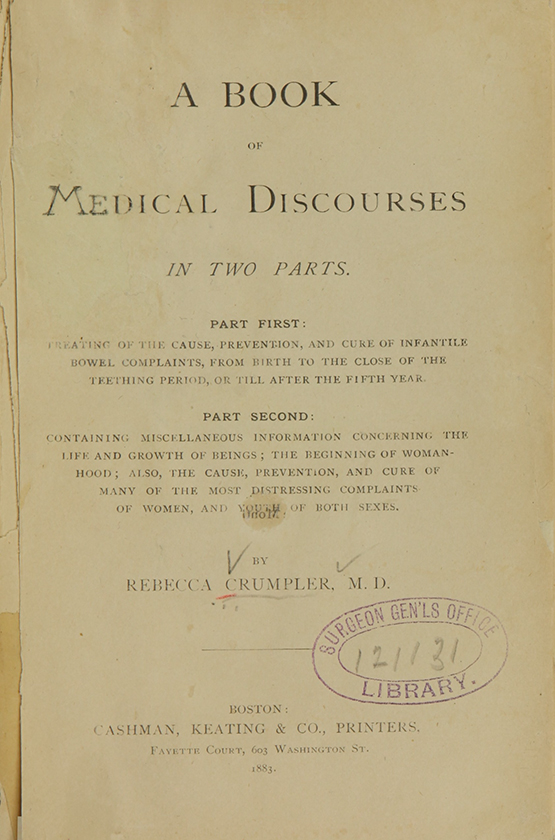

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

Rebecca Lee Crumpler challenged the prejudice that prevented African Americans from pursuing careers in medicine to became the first African American woman in the United States to earn an M.D. degree, a distinction formerly credited to Rebecca Cole. Although little has survived to tell the story of Crumpler’s life, she has secured her place in the historical record with her book of medical advice for women and children, published in 1883.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 0

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

Susan La Flesche Picotte was first person to receive federal aid for professional education, and the first American Indian woman in the United States to receive a medical degree. In her remarkable career she served more than 1,300 people over 450 square miles, giving financial advice and resolving family disputes as well as providing medical care at all hours of the day and night.

Susan La Flesche, early 1900s, when she returned to the Omaha Reservation

Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 0

Dr. Rebecca J. Cole

In 1867, Rebecca J. Cole became the second African American woman to receive an M.D. degree in the United States (Rebecca Crumpler, M.D., graduated from the New England Female Medical College three years earlier, in 1864). Dr. Cole was able to overcome racial and gender barriers to medical education by training in all–female institutions run by women who had been part of the first generation of female physicians graduating mid–century. Dr. Cole graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1867, under the supervision of Ann Preston, the first woman dean of the school, and went to work at Elizabeth Blackwell’s New York Infirmary for Women and Children to gain clinical experience.

National Library of Medicine

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 0

Dr. Rebecca J. Cole

Dr. Rebecca J. Cole was the first African American woman to receive an MD in the United States.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Cole.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Rebecca J. Cole Sadly, as is the case with many records of the achievements of African Americans of her generation, no images have survived of Dr. Rebecca J. Cole. She was the second African American woman to receive an M.D. degree in the United States, in 1867. Rebecca Cole was born and raised in Philadelphia. She completed her secondary education at the first co-educational high school for African Americans in the city. She enrolled at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania near the end of the Civil War. She trained with Dr. Ann Preston, the first woman dean of the school, and in 1867, was the first African American to graduate. Dr. Cole, like many of her fellow women students of medicine was able to continue her training by joining an institution founded for women patients and practitioners. To gain clinical experience, she took a job at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, established by physicians Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister Emily, with the help of Dr. Marie Zakrzewska. Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell assigned Dr. Cole the role of health visitor in the local community. She was responsible for dispensing practical advice to mothers living in poverty about the best ways to keep their families healthy. Dr. Blackwell thought Dr. Cole had the ideal character for such work, and mentioned in her autobiography that she had “carried on this work with tact and care.” Dr. Rebecca Cole practiced in South Carolina for a number of years, before returning to Philadelphia. In 1873, she opened a Women’s Directory Center to provide medical and legal services to women and children in need. In January 1899, Dr. Cole was appointed superintendent of a home in Washington, D.C. run by the Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children. In her years of caring for families living interrible poverty in the city of Washington, she was most appreciated for the difference she was able to make. As mentioned in one of the annual reports from the association:"Dr. Cole herself has more than fulfilled the expectations of her friends. With a clear and comprehensive view of her wholefield of action, she has carried out her plans with the good sense and vigor which are a part of her character."

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 0

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens

In 1950, Dr. Helen Dickens was the first African American woman admitted to the American College of Surgeons. The daughter of a former slave, she would sit at the front of the class in medical school so that she would not be bothered by the racist comments and gestures made by her classmates. By 1969, she was associate dean in the Office for Minority Affairs at the University of Pennsylvania, and within five years had increased minority enrollment from three students to sixty–four.

National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B07139

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 6 of 0

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens

Dr. Helen Dickens was the first African American woman admitted to the American College of Surgeons. She served communities with limited access to health care, provided sex education to women living in poverty, and worked as a professor of surgery.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dickens.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens Dr. Helen Dickens began her medical career by providing care to those who had no means to obtain treatment. Once, as she visited a house without electricity, she had to drag a bed to the window to deliver a baby by the light from the streetlight outside. Because her parents had struggled to make a living in low-paying jobs, they insisted that their daughter receive a good education. She attended a desegregated high school, applied to the best schools and hospitals and was not intimidated by the idea of training at predominantly white schools. In 1934, when she earned her M.D. from the University of Illinois, Dr. Helen Dickens was the only African American woman in her class. She completed her internship at Provident, a black hospital on the south side of Chicago. Working among the poor, she treated tuberculosis and provided obstetric and gynecological care. Moving to Philadelphia, Dr. Dickens worked for six years at Aspiranto Health Home, treating patients living in poverty, with little access to medical care. To expand her training in obstetrics and gynecology, she returned to Provident Hospital in Chicago. In 1943, she married a fellow resident, Dr. Purvis Sinclair Henderson. They moved to New York City and Dr. Dickens began a residency at Harlem Hospital. She left to get a Master of Science degree from the University of Pennsylvania, then returned to complete her residency at Harlem in 1946. Four years later, Dr. Helen Dickens became the first African American woman to be named a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons. Throughout her career, Dr. Dickens focused on the problems she had seen in her obstetrics and gynecology practice. She wanted to educate young women to give them the knowledge to control their fertility and sexual health. Her extensive research resulted in intervention strategies to help schools, parents, and health professionals reduce the incidence of teen pregnancies, and sexually transmitted diseases. Moving back to Philadelphia, Dr. Dickens taught at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1969, she was appointed Dean of the Office for Minority Affairs. In that role, she reached out to minority students to encourage them to pursue medical careers. Thanks largely to her efforts, minority student enrollment increased from just three students to sixty-four within five years. In 1985, Dr. Helen Dickens was named Professor Emeritus.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 7 of 0

Dr. Eliza Ann Grier

Eliza Ann Grier was an emancipated slave who faced racial discrimination and financial hardship while pursuing her dream of becoming a doctor. To pay for her medical education, she alternated every year of her studies with a year of picking cotton. It took her seven years to graduate. In 1898, she became the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia, and although she was plagued with financial difficulties throughout her education and her career, she fought tenaciously for her right to earn a living as a woman doctor.

Archives and Special Collections on Women in Medicine, Drexel University College of Medicine

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 8 of 0

Dr. Eliza Ann Grier

Dr. Eliza Ann Grier was the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Grier.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Eliza Ann Grier Dr. Eliza Ann Grier had once been a slave. She went on to become the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia. After emancipation, Eliza Grier decided to become a teacher, studying for seven years at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. But she aspired to a career as a physician, believing she could be of most benefit to others and earn a fair wage if she had a medical education. “When I saw colored women doing all the work in cases of accouchement ... or, childbirth and all the fee going to some white doctor who merely looked on, I asked myself why should I not get the fee myself.” So, in December of 1890, Eliza Grier wrote to the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. “I have no money and no source from which to get it,” she wrote, “Only as I work for every dollar.” She asked the dean “if there was any possible way for an emancipated slave to receive any help into so lofty a profession.” She was admitted, but to pay the tuition, Eliza Grier alternated each year of study with a year of picking cotton. Despite these hardships, she did not lose sight of her goal. After seven years of work and study, she graduated in 1897, and returned to Atlanta. Later that year, Dr. Eliza Ann Grier became the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia. After only four years, Dr. Grier fell ill and was unable to maintain her medical practice. Determined to keep up with her work, she called on various supporters for help. She wrote to Susan B. Anthony, leader of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, to ask for her help, but died soon thereafter. As she said in 1898: “I went to Philadelphia, studied medicine hard, procured my degree, and have come back to Atlanta, where I have lived all my life, to practice my profession... Some of the best white doctors in the city have welcomed me, and say that they will give me an even chance in the profession. That is all I ask.” The North American Medical Review reported: “She will hang out her shingle for general practice, and says she will make no discrimination on account of color.” Dr. Eliza Grier realized a remarkable achievement.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Setting Their Sights

Confronting Glass Ceilings

By the early 1900s, women had made impressive inroads into the medical profession as physicians, but few had been encouraged to pursue careers as medical researchers. To succeed as scientists, despite opposition from male colleagues at leading institutions, women physicians persisted in gaining access to mentors, laboratory facilities, and research grants to build their careers.

The achievements of these innovators often went unrewarded or unacknowledged for years. Yet these resourceful researchers carved paths for other women to follow and eventually gained recognition for their contributions to medical science.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 0

Dr. Florence Rena Sabin

Florence Rena Sabin was one of the first women physicians to build a career as a research scientist. She was the first woman on the faculty at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, building an impressive reputation for her work in embryology and histolology (the study of tissues). She also overturned the traditional explanation of the development of the lymphatic system by proving that it developed from the veins in the embryo and grew out into tissues, and not the other way around.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

-

Microscope like the ones Florence Sabin used, 1917

The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions-

ReadBiography

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

-

-

Looking for Answers

Dr. Florence Sabin examined chick embryos at various stages of growth. She was the first to explain exactly how embryonic cells evolve into blood vessels, blood serum, and red blood cells.

National Museum of Health and Medicine

-

ReadBiography

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

-

Dr. Sabin's Microscope

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 0

Dr. May Edward Chinn

In 1926, May Edward Chinn became the first African American woman to graduate from the University and Bellevue Hospital Medical College. She practiced medicine in Harlem for fifty years. A tireless advocate for poor patients with advanced, often previously untreated diseases, she became a staunch supporter of new methods to detect cancer in its earliest stages.

George B. Davis, Ph.D.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 0

Dr. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori

Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori and her husband, Dr. Carl Cori, were the first married couple to receive a Nobel Prize in science. Gerty Cori was only the third woman ever to win a Nobel Prize, and was the first woman in America to do so.

Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 0

Dr. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori

Dr. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori became the first women in America to win a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Cori.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Gerty Radnitz Cori was the first American woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Medicine. She and her husband, Dr. Carl Cori, shared the prize for their discovery of the cycle of carbohydrates in the human body. They had been classmates at the German University of Prague, where Gerty Cori was one of only a few women students. She received her M.D. in 1920. The couple married and began to work in clinics in Vienna. In 1922, concerned that war would break out in Europe for a second time, they immigrated to Buffalo, New York. Carl Cori accepted a position at the State Institute for the Study of Malignant Diseases. Gerty Cori joined him six months later, after securing a job as an Assistant Pathologist. Although the couple was frequently discouraged from working together, they had a dynamic research partnership that proved immensely profitable in their work. Specializing in biochemistry, the husband and wife team began to study how glucose is metabolized in the human body. In 1929, they developed their theory of “the cycle of carbohydrates,” now known as the Cori Cycle. The theory explains how carbohydrates supply energy to muscles during exercise, and then are regenerated and stored until needed again by the muscles. It was the first time the cycle of carbohydrates in the human body had been fully explained and understood, and proved especially useful for the treatment of diabetes. Despite their collaborative partnership in defining the cycle, Carl Cori initially received more professional recognition than Gerty Cori. He was encouraged to abandon the team approach and work alone. He was even offered a job only on the provision that he stop working with his wife. The Cori’s continued in their successful collaboration, however, and in 1931 moved to St. Louis. Carl Cori took up the post of Chair of the Pharmacology Department at Washington University School of Medicine. Over the next sixteen years, Gerty Cori worked alongside him as a research assistant. Together, they made further discoveries that clarified the processes of carbohydrate metabolism, that they had originally laid out in the description of the Cori Cycle. In the mid-1940s, Carl and Gerty Cori received great recognition for their work. Carl Cori was appointed Chair of the new Biochemistry Department in 1946, and Gerty Cori was appointed to a full professorship. The following year, they were awarded the Nobel Prize for the Cori Cycle. They were the first married couple ever to win the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 0

Dr. Louise Pearce

Louise Pearce, M.D., a physician and pathologist, was one of the foremost women scientists of the early 20th century. Her research with pathologist Wade Hampton Brown led to a cure for trypanosomiasis (African Sleeping sickness) in 1919.

Courtesy of the Rockefeller University Archives

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 6 of 0

Dr. Louise Pearce

Dr. Louise Pearce’s research helped lead to a cure for trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness) in 1919.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Pearce.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Louise Pearce volunteered to go alone to the Belgian Congo in 1920 to test a new drug she hoped would cure African sleeping sickness, a disease that was often fatal. She received her M.D. from The Johns Hopkins University in 1912. Looking for work, she wrote to Dr. Simon Flexner, Director of the Rockefeller Institute in New York City, requesting a research position. Dr. Flexner supported her application, and Dr. Louise Pearce became the first woman to work directly with him. In 1910, an arsenic-based drug called Salvarsan was found to be an effective treatment for syphilis. Scientists had hopes of developing other arsenic-based drugs. Dr. Flexner asked his research team to try and find an arsenical compound for use against African sleeping sickness. They succeeded. Tryparsamide, they found, destroyed the infectious agent of sleeping sickness in animals. In 1919, these results were announced in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. A severe outbreak of African sleeping sickness broke out in the Belgian Congo in 1920. While in Africa, Dr. Pearce administered and studied the effects of the tryparsamide on seventy patients. The results were spectacular: the parasites were driven from circulating blood within days and totally eradicated within weeks. Symptoms cleared up and general health was restored in a large proportion of even the most severe cases. Belgian officials were impressed by the results. Dr. Pearce was awarded the Ancient Order of the Crown and elected a member of the Belgian Society of Tropical Medicine. Three decades later, in 1953, she was invited to Brussels to receive the King Leopold III Prize and an award of ten thousand dollars. After her success in the Belgian Congo, Dr. Pearce returned to the Rockefeller Institute, and was promoted to Associate Member in 1923. Teamed with Dr. Wade Hampton Brown, she studied susceptibility and resistance to infection. They discovered they could transplant certain cancers from one rabbit to another. The Brown-Pearce tumor was the first known transplantable tumor, aiding research into malignant tumors in cancer laboratories around the world. By 1940, more than two dozen hereditary diseases and deformities were studied in the tumors of the research team’s rabbits. After the death of Wade Hampton Brown in 1942, Dr. Pearce focused on writing up their research findings, until her retirement in 1951. After a short illness, she died at her home in New Jersey in 1959.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 7 of 0

Dr. Anna Wessels Williams

Anna Wessels Williams, M.D., worked at the first municipal diagnostic laboratory in the United States, at the New York City Department of Health. She isolated a strain of diphtheria that was instrumental in the development of an antitoxin for the disease. She was a firm believer in the collaborative nature of laboratory science, and helped build some of the more successful teams of bacteriologists, which included many women, working in the country at the time.

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 8 of 0

Dr. Anna Wessels Williams

Dr. Anna Wessels Williams isolated a strain of bacteria that scientists used to develop the treatment for diphtheria.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Wessels Williams.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

In the 1800s, diphtheria was a deadly infectious disease without cure. Dr. Anna Wessels Williams isolated a strain of the diphtheria bacillus crucial to the development of an antitoxin that helped eradicatethe disease in New York City. Dr. Williams worked at the New York City Department of Health, in the first municipal diagnostic laboratory in America. She researched the spread of infectious diseases like diphtheria and polio, then sought ways to protect people and lower the rates of infection. Dr. William H. Park was the director of the lab, and the two collaborated. Together, they worked on developing an antitoxin for diphtheria. In her first year of work, Dr. Williams isolated the strain and by the fall of that year, physicians across Manhattan issued the diphtheria antitoxin free of charge, helping to eradicate the disease among the city’s poor. Dr. Williams was appointed to a full-time staff position as assistant bacteriologist. She shared credit with William H. Park for the discovery, which became known as the Park-Williams Strain. She recognized the collaborative nature of laboratory research, and later said she was “happy to have the honor of having my name thus associated with Dr. Park.” In 1896, Dr. Williams traveled to the Pasteur Institute in Paris hoping to develop an antitoxin for scarlet fever. The research going on in Paris inspired her, and she became interested in rabies. Returning to the U.S., she brought back a culture of the rabies virus and worked to develop a better way to diagnose it. Her method surpassed the original test, and became the model technique for the next thirty years. She was promoted to Assistant Director of the New York City Department of Health laboratory in 1905 and continued to work alongside Dr. Park. Together they wrote a textbook on micro-organisms for students, physicians, and health officers that quickly became a classic text. In 1929, they published “Who’s Who Among the Microbes,” thought to be one of the earliest books on the topic written especially for the public. In 1914, Dr. Williams was elected president of the Women’s Medical Society of New York. In 1931, she was elected to the laboratory section of the American Public Health Association, and the following year became the first woman appointed chair of the section. In addition to her groundbreaking research, she helped build some of the most successful teams of bacteriologists—including many women—working in the country at the time.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 9 of 0

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright

Dr. Jane Wright analyzed a wide range of anti–cancer agents, explored the relationship between patient and tissue culture response, and developed new techniques for administering cancer chemotherapy. By 1967, she was the highest ranking African American woman in a United States medical institution.

National Library of Medicine

-

ReadBiography

-

DigitalCollections

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 10 of 0

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright

Dr. Jane Cook Wright advanced chemotherapy techniques through her pioneering cancer research.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Wright.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Jane Wright made her mark in cancer research, developing new techniques for administering chemotherapy and evaluating new treatments for the disease. Jane Wright grew up in a wealthy and prestigious family in New York City. Her father, Dr. Louis Wright, was one of the first black graduates of Harvard University Medical School. In the late 1930s, he founded the Cancer Research Center at Harlem Hospital where Jane Wright would later do some of her most important medical research. Jane Wright grew up during the Harlem Renaissance. African American artists, musicians, writers, and political activists were celebrating their culture, and challenging America’s racial barriers. In a time of great aspirations, Jane Wright was fortunate to have the support and guidance of her family, as well as access to a fine education. Smith College offered her a four-year academic scholarship to study art. In her junior year, at her father’s request, she changed her major to pre-med. She enrolled on a full academic scholarship at New York Medical College where the majority of students were white. Jane Wright was elected president of the Honor Society and vice president of her class. She graduated with honors in 1945. Four years later she joined her father, then the Director of the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital. Together, they experimented with different chemical agents on leukemia in mice. While her father worked in the lab, she performed patient trials. In 1949, the Wrights began treating patients with anti-cancer drugs. Several patients experienced some degree of remission. When her father died in 1952, Dr. Jane Wright succeeded him as director. In 1955, she joined the faculty of New York University as an Associate Professor of Surgical Research, and Director of Cancer Research. There, she continued her work with chemotherapy studying a variety of anti-cancer drugs and developing new techniques for delivering potent drugs to tumors deep within the body. She created a database, cross-referencing cancers and patients, to help determine the effectiveness of these drugs. Later, Dr. Wright began experimenting with combinations of anti-cancer drugs. Because she believed most cancers were caused by viruses, she investigated a new class of anti-cancer agents comparable to antibiotics. During her forty-year career, she produced more than seventy-five research papers on cancer chemotherapy, and in 1971, became the first woman elected president of the New York Cancer Society.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Making Their Mark

Bringing fresh perspectives to the profession of medicine, women physicians often focused on issues that had received little attention-the social and economic costs of illness, new research and treatments for women and children, and the low numbers of women and minorities entering medical school and practice.

As the first to address some of these needs, women physicians often led the way in designing new approaches to public health policy, illness, and access to medical care. The revival of the civil rights and women's movements and passage of equal opportunity legislation in the 1960s led to a dramatic increase in the numbers of women and minorities entering medicine.

Making Their Mark

Caring for Communities

Many early advocates of the rightful place of women in the professions argued that women had a special obligation to those most at risk. By the first decades of the 1900s, women physicians were establishing innovative public health programs and labor reforms designed to protect the most vulnerable members of society.

By succeeding in work considered “unsuitable” for women, these leaders overturned prevailing assumptions about the supposedly lesser intellectual abilities of women and the traditional responsibilities of wives and mothers. [or As the century progressed, the discrimination experienced by women and minorities fueled broad social movements for change. Women physicians involved in this struggle became advocates for those suffering from neglect or abuse.]

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 0

Dr. Alice Hamilton

Alice Hamilton was a leading expert in the field of occupational health. She was a pioneer in the field of toxicology, studying occupational illnesses and the dangerous effects of industrial metals and chemical compounds on the human body. She published numerous benchmark studies that helped raise awareness of dangers in the workplace. In 1919, she became the first woman appointed to the faculty at Harvard Medical School, serving in their new Department of Industrial Medicine. She also worked with the state of Illinois, the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the League of Nations on various public health issues.

Alice Hamilton, M.D., National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B014009

-

ReadBiography

-

DigitalCollections

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 0

Dr. Martha May Eliot

Dr. Martha May Eliot worked for the Children’s Bureau, a national agency established in 1912 to improve the health and welfare of American children, for over 25 years. First employed as director of the bureau’s Division of Child and Maternal Health, Eliot went on to become assistant chief, and then chief, of the whole organization. She was the only woman to sign the founding document of the World Health Organization, and an influential force in children’s health programs worldwide.

Martha May Eliot, M.D., National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B09844, photograph by Bachrach

-

ReadBiography

-

DigitalCollections

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 0

Healthy femur (left) and femur showing the effects of rickets (right)

Children’s bones contain growth plates—areas of soft cartilage that lengthen before being replaced by hard bone. With rickets, the bone's growth plate widens as soft cartilage cells accumulate.

The bones of a child with rickets (right) are too soft and bend under the pressure of body weight. Proper diet and adequate sunlight provide the vitamin D necessary to build strong bones (left). Dr. Martha May Eliot’s work provided insight on how to treat this disease.

National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 0

Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias

Through her efforts to support abortion rights, abolish enforced sterilization, and provide neonatal care to underserved people, Helen Rodriguez–Trias expanded the range of public health services for women and children in minority and low–income populations in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Helen Rodriguez–Trias, M.D., JoEllen Brainin–Rodriguez M.D., photograph by Rafael Pesquera

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 0

Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias

Dr. Helen Rodriguez–Trias worked to improve access to health services for women and children in underserved communities, advocated for women’s rights, and served as the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Rodriguez–Trias.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript

Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias wanted to study medicine because it combined the things she loved the most—science and people. She graduated from the University of Puerto Rico in 1959 and moved to New York, where she married and had three children. After seven years, she returned to the University of Puerto Rico to study medicine. She saw it as a direct way to contribute to society—by helping individuals instead of working through groups or organizations. She received an M.D. with the highest honors in 1960. During her residency, Dr. Rodriguez-Trias established the first center in Puerto Rico for the care of newborn babies. Under her direction, the hospital’s death rate for newborns decreased 50 percent within three years. In 1970, she returned to New York City to serve the Puerto Rican community in the South Bronx. Working at Lincoln Hospital, she led community campaigns against lead paint, unprotected windows and other health hazards. She also taught at City College, raising students’ awareness of the real conditions in the neighborhoods they served. Dr. Rodriguez-Trias saw the critical links between public health and social and political rights, and expanded her work to a broader international community. She said, “I think my sense of what was happening to people’s health... was that it was really determined by what was happening in society— by the degree of poverty and inequality you had.” Working as an advocate for women’s reproductive rights, she campaigned for change at a policy level. She worked especially for low-income populations in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. She fought for reproductive rights, worked with women with HIV, and joined the effort to stop sterilization abuse. Government-sponsored sterilization programs led to hundreds of unwanted sterilizations. (Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias) “Sterilization has been pushed really internationally as a way of population control. And there is a difference between population control and birth control. Birth control exists as an individual right. It’s something that should be built into health programming. It should be part and parcel of choices that people have. And when birth control is really carried out, people are given information, and the facility to use different kinds of modalities of birth control. While population control is really a social policy that’s instituted with the thought in mind that there’s some people who should not have children or should have very few children, if any at all. I was working in Puerto Rico in the medical school in those years, the decade of 1960 to 1970. And one of the things that seemed pretty obvious to us then was that Puerto Rico was being used as a laboratory. And it was being used as a laboratory for the development of birth control technology.” In 1979, Dr. Rodriguez-Trias testified before the Department of Health, Education and Welfare for the passage of federal sterilization guidelines, which she helped to draft. These require a woman’s consent to sterilization, offered in a language she can understand, and set a waiting period between the consent and the operation. Toward the end of her life, she said, “I hope I’ll see in my lifetime a growing realization that we are one world. And that no one is going to have quality of life unless we support everyone’s quality of life. Not on a basis of do-goodism, but because of a real commitment. It’s our collective and personal health that’s at stake.” In 2001, President Clinton presented her with a Presidential Citizen’s Medal for her work on behalf of women, children, people with HIV and AIDS, and the poor. Later that year, Helen Rodriguez-Trias died of complications from cancer.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 0

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone brought an uncomfortable subject to the forefront of public debate in her work in sex education. Beginning in the 1950s, when public discussion of such issues was considered highly controversial, Dr. Calderone flouted convention by speaking out in the first place, and as a woman broaching such a topic. In 1964, she founded the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), to promote sex education for children and young adults.

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 6 of 0

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone advocated for sex education, founding the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS).

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Calderone.

-

ReadBiography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Transcript