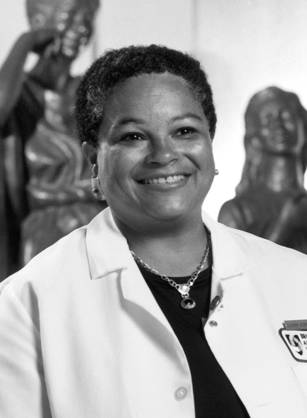

Biography: Dr. JudyAnn Bigby

JudyAnn Bigby, M.D., served as director of the Harvard Medical School Center of Excellence in Women's Health. She is devoted to the health care needs of underserved populations, focusing especially on women's health. She is also nationally recognized for her pioneering work educating physicians on the provision of care to people with histories of substance abuse.

JudyAnn Bigby graduated from Wellesley College, and earned her doctor of medicine degree at Harvard Medical School in 1978. Born in Jamaica, New York, Bigby and her siblings were the first in their family to attend college, and she was the first to become a doctor. After medical school, Bigby completed a primary care internal medicine residency at the University of Washington Affiliated Hospitals in Seattle and was a Henry J. Kaiser Fellow in general internal medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital. She joined the faculty of the department of medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard in 1984, and was active in teaching, patient care, research, and administration. She was also medical director of Community Health Programs at Brigham and Women's Hospital, and an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Bigby became interested in helping the underserved in her clinical practice. Seeing that many of her patients' problems could not be solved in her office, she set out to encourage fellow physicians to take into account their patients' personal background (gender, race, ethnicity, and other factors), and their situation in the wider community. As a medical educator she strives to create innovative teaching models, exploring substance abuse, social factors in health and well-being, the relationship of race and ethnicity to health and illness, and the role of communities in maintaining the health of population groups.

Dr. Bigby works to convince medical professionals to adopt her concerns. Medical students and residents often see alcoholics and drug addicts as stereotypical "skid row," manipulative patients. She tries to develop teaching strategies that challenge this view, as well as providing the medical training. She works with public health officials, community health centers, and other community-based organizations in the Boston area to explore models of care for underserved women, particularly those with breast and cervical cancer, and seeking ways to decrease racial disparities in health care.

Dr. Bigby has experienced many challenges as a woman physician, challenges that have varied at different stages of her career. Balancing family and a medical career is one such challenge. Dr. Bigby had the first of her two children during medical school, at a time when few women were even enrolled in medical school. She also discovered that, in the medical profession, there is an expectation that personal problems — major illness, family issues, or other events — should not interfere with a physician's work. Her physician husband's commitment to sharing the responsibility for raising their children has helped her to balance work and family life.

Dr. Bigby has volunteered her time on Boston's Public Health Commission, the Women's Education and Industrial Union, the Medical Foundation, and the Center for Community Health, Education, Research, and Service, among other programs. She is a member of the Institute of Medicine's Committee Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century and the Minority Women's Health Panel of Experts for the Department of Health and Human Service's Office on Women's Health. She served on the Council of Graduate Medical Education from 1994 to 1999.

What was my biggest obstacle?

As a generalist, I am frequently challenged by the breadth of issues facing patients and thus medical students and other learners...Advice to take a narrow path in my career is contradicted by what I see as a primary care physician—the limitations of medicine in addressing the health needs of individuals and communities.

How do I make a difference?

While I have developed several nationally recognized curricula in the diagnosis and management of substance abuse in primary care, I am convinced that the real impact of my work lies in the more than 300 faculty across the country who have acquired new knowledge and skills and continue to educate others, thus multiplying the impact in a way that a written curriculum cannot achieve.

Asterix Dr. JudyAnn Bigby

Asterix Dr. JudyAnn Bigby

I see patients part-time. I only spend two mornings a week seeing patients. And with all my other responsibilities, I keep doing that because my patients are the ones who inspire me. I see mostly women. I have a lot of women of color, who may not be that well off, and you know, they are really incredible people. They have a lot of adversity in their lives—they are very ill, many of them, but they have so much positive that they think about their lives. So that's one thing that keeps me going and inspires me. One of the things that I am trying to do is to try to get physicians to see things from the patient's perspective. Not just how it feels to have a heart attack, or breast cancer, or something like that. But also how the circumstances of a patient's life impacts everything that happens to them, from the moment they walk into a health care facility. It may determine how comfortable they feel speaking to the secretary. It may determine how comfortable they feel asking a doctor a question. It may impact how comfortable they feel accepting instructions or advice from a doctor. They may decide that because of a past experience, or a family member's experience, that they aren't going to trust that doctor and not follow the advice. In our study, where we were trying to find out what types of things contribute to dissatisfaction with doctors by women of color—Black and Latina women—we found that both doctors and patients make assumptions about each other. The women seemed more aware that they were making the assumptions; they felt that race was a very important issue in the way that they built their assumptions. The doctors did not feel that they were making assumptions based on race, but on other issues. But in the end, what happens is, because of these assumptions, when the two individuals are communicating, they're not communicating about it the same way. Their assumptions are different. It definitely colors the way they interact with the other person. And I think that one of the things that needs to happen is people need to be able to recognize their assumptions and talk about them, so that people can get on the same page when they're communicating. For those people who are worried that healthcare is such a negative field now—because of managed care, or not being paid enough money, or having a lot of pressure to see more patients—I think that we need people to go into medicine who will turn around and say, 'Well, if this is not the right way to do it, if this is not best for the patients, then we have to change.' And we need more people like that.