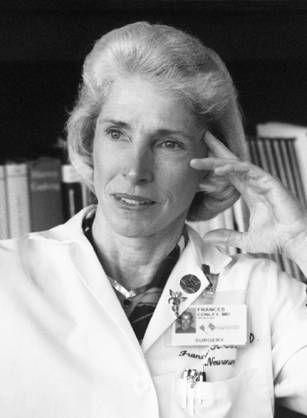

Biography: Dr. Frances K. Conley

Year: 1966

Achievement: Dr. Frances Conley was the first woman to pursue a surgical internship at Stanford University Hospital.

Year: 1988

Achievement: Dr. Frances Conley was the first woman to be a tenured full professor of neurosurgery at a medical school in the United States.

When I was young, our family doctor was a female general practitioner (unusual in those days) and I remember both awe and dread at visits to her office... To a child, she exuded tremendous power reflected in pills, injections, pain, and soothing. Perhaps her example guided my unconscious career choice; I can think of no other reason for it. Early in my teenage years I had decided I wanted to be a doctor, not just a "Mrs.," although I certainly anticipated marriage as well.

When I started medical school, I had never envisioned pursuing a nontraditional career path... I did not deliberately choose to buck the system and defy the status quo, but I was mesmerized, truly fascinated, by surgery... Unexpectedly, I fell in love with the bright lights of the operating theater, the world of sterile instruments, the drama of life and death, the actors—decisive, cool under pressure, with magic hands.

In 1966, Frances Krauskopf Conley became the first woman to pursue a surgical internship at Stanford University Hospital, and in 1986 she became the first woman to be appointed to a tenured full professorship of neurosurgery at a medical school in the United States. In 1991, she risked her career when she drew public attention to the sexist environment which, she argued, pervaded Stanford University Medical Center.

Frances Krauskopf was born in 1940 in Palo Alto, California, and grew up on the Stanford campus, where her father was a professor of geochemistry. "Early in my teenage years I had decided I wanted to be a doctor, not just a 'Mrs.,' although I certainly anticipated marriage as well. When I was young, our family doctor was a female general practitioner (unusual in those days) and I remember both awe and dread at visits to her office... To a child, she exuded tremendous power reflected in pills, injections, pain, and soothing. Perhaps her example guided my unconscious career choice; I can think of no other reason for it."

She attended Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, where she was inspired by women of accomplishment. "At Bryn Mawr, I learned I had the intelligence to do whatever I wanted in life," she remembered. She returned to Stanford in her junior year, and entered medical school there in 1961, where she was one of twelve women in a class with sixty men. She quickly observed differences in the way male and female students were treated and noticed that male physiology was used to define what was "normal" in medical models. She also became fascinated with surgery. "When I started medical school," she said, "I did not deliberately choose to buck the system and defy the status quo, but I was mesmerized, truly fascinated, by surgery... Unexpectedly, I fell in love with the bright lights of the operating theater, the world of sterile instruments, the drama of life and death, the actors decisive, cool under pressure, with magic hands."

She was discouraged from pursuing what was then an almost exclusively male specialty, but was not dissuaded, and completed her M.D. degree in 1966. That same year, she became the first woman to start a rotating surgical internship at Stanford University Hospital. She completed her residency there in neurological surgery in 1975, and in 1977 became the fifth woman to be certified by the American Board of Neurological Surgery.

While at Stanford, Frances Krauskopf met and later married Phil Conley, a businessman and track star who had represented the United States in the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. She made her own wedding gown for the ceremony. Dr. Conley too earned distinction as an athlete in 1971, when she became the first woman to finish the San Francisco Bay to Breakers 7.8-mile race.

As one of the few female neurosurgeons in the United States, Dr. Conley often experienced sexism in the hospital environment. In 1991, she made national headlines when she announced her intention to resign her tenured position as professor of neurosurgery at Stanford University Medical School in protest against the sexist attitudes of a male colleague who had recently been promoted. "This is a pervasive, global problem for women who are trying to get into professional careers," she said in an interview for Time magazine. She emphasized the distinction between outright sexual harassment and "gender insensitivity," which she considered the larger and more insidious problem. Women in medical schools around the country reported similar problems, including men calling women physicians "honey" rather than "doctor," or groping them after they had scrubbed for surgery and could not use their hands to resist.

Soon after Conley announced her intention to resign, Stanford adopted policies to deal with gender insensitivity. She withdrew her resignation and continued a distinguished career in teaching and clinical research at Stanford, winning many awards and honors, including the Kaiser Award for Excellence in Teaching in 1992. Dr. Conley chaired both the University Advisory Board, from 1994 to 1995, and the Senate of the Academic Council, from 1997 to 1998, positions in which she worked with colleagues to review academic appointments and influence university policies. She also headed the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Heath Care System, from 1998 to 2000, and in 1998 published, Walking Out on the Boys, a book about her experiences as a women surgeon and the sexism in the medical profession.

What was my biggest obstacle?

Sexism — on both the individual and the institutional level — in my medical training and in my university hospital.

In medical school, more often, as women, we were ignored, even if we had the right answer... The women in my class learned to deflect a few of the insistent, almost daily insults, but we absorbed many more offensive slights that had little to do with bad performance and everything to do with fortune of birth.

In the 1960s almost no surgical programs were taking any women into their ranks, let alone into neurosurgery. There were no prohibitive written policies in place — women were just not expected to have any interest in surgery, and certainly did not belong there.

How did I make a difference?

What I have done, I hope, is help others open up a dialogue about gender insensitivity. If we can get men and women to start talking to one another about what gender insensitivity means, then we will have accomplished a great deal.

Who was my mentor?

At Bryn Mawr I saw women as professors and student body presidents, women who sparkled with wit and intelligence and were highly motivated to do something important with their lives. At Bryn Mawr I learned I had the intelligence to do whatever I wanted in life.

Asterix Dr. Frances K. Conley

Asterix Dr. Frances K. Conley

I had a number of professors who tried to talk me out of my decision to pursue a career in surgery, and I'm not exactly sure why, although I think that their perception of the lifestyle of the surgeon was not compatible with being a woman. At that point I was married, and I'm sure that the general assumption at that time was that if you're married you are going to have a family, and that the two-a career in surgery and having a family-were incompatible.

Surgery is just such fun. It is a wonderful discipline because you get a chance to do your thinking beforehand. You have to make fairly rapid decisions, and you have to live by those decisions. And what I really enjoyed about it was the planning and execution of "the perfect case." Of doing things meticulously, correctly, efficiently, and having a very happy outcome with it. And one's ego gets very involved in surgery. And I guess my ego needed to be fed, and surgery did that for me very well. In 1991, I gave up my position as a tenured full professor of neurosurgery at the Stanford Medical School. And I did so because a person was elevated to be the chair of my department who I felt was a very sexist person.

The dean had articulated the desire to create an environment at the medical school that was more hospitable to those of us who were different-i.e., women and minorities. And his putting this person into a position of the deanship was antithetical to what he had espoused as his intent. And so I quit.

I had tremendous power at that particular time. I was a tenured full professor. And there were very few tenured full professors that were women who were neurosurgeons. I had been elected to a number of things at the University so I was very well known, and had a lot of support behind me, so that I dealt my hand with a fair amount of power behind it. The difference that I made when I took a stand on looking at or exploring the differential treatment that women received in medicine-the difference was, that it woke people up. All of a sudden, that which had been just accepted as part of the medical world, as normative behavior-that you can pat nurses on their butts, and you call people "honey" in front of patients, and that you can do this-that was normative behavior, and nobody questioned it. And I think the difference that I created was it made people stop in their tracks, and it made them think, Hey, is this right? Am I treating my women patients the same way I do my men patients-with respect, and with dignity-and am I giving them as much of me as I should be giving them? And so from that point of view, yes, I think it did make a big difference. Did I correct things? No, not totally.