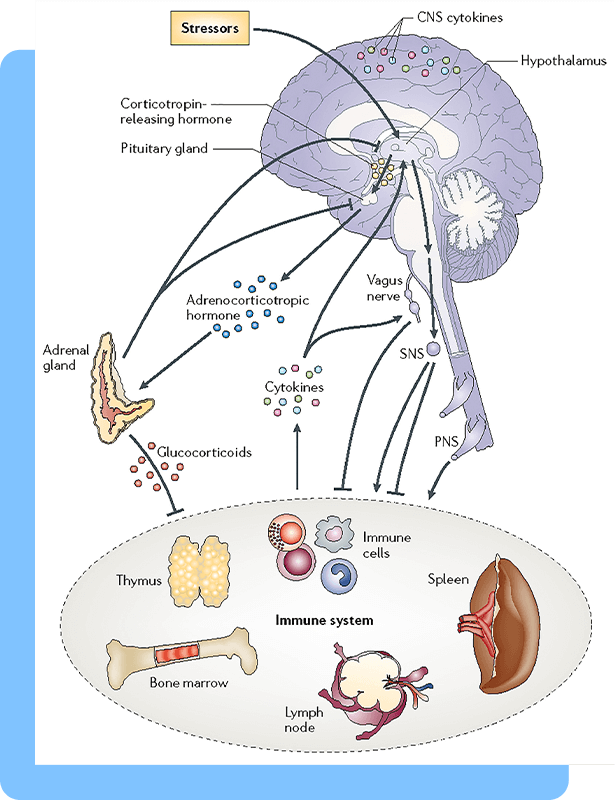

Groddeck forcefully advocated for the view that the psychological mechanism for hysterical conversion could be generalized to the entire range of somatic or bodily disease. He argued that symptoms in any organic disorder could be interpreted like hysterical symptoms, as symbolic expressions of unconscious wishes manifested in the patient's body.

[Left page]

4

Georg Groddeck

[…]used of the Gymnasium in which I followed my classical studies, and where I suffered much that I should have to tell you of, if I were concerned to make you understand the unfolding of my nature. That, however, is not what is in my mind, but only the fact that I attributed all the hatred and the suffering of my schooldays to science, because it is more convenient to ascribe one’s depression to external events than to seek its roots in the depths of the unconscious.

Later, only very late, did it become clear to me that the expression “Alma Mater,” nursing mother, recalled the earliest and the hardest conflict of my life. My mother had nursed only her eldest child; at that time she was visited with severe inflammation of the breasts which atrophies the milkglands. My birth must have taken place a day or two earlier than was expected. In any case, the wet-nurse who had been engaged for me was not yet in the house, and for three days I was scantily nourished by a woman who came twice a day in order to feed me. That did me no harm, one might say, but who can judge the feelings of a suckling babe? To have to go hungry is not a kind welcome for a new-born infant. Now and then I have become acquainted with people who have had a like experience, and even if I cannot prove that they suffered mental harm thereby, still it seems to me quite probable that they did. And by comparison with them I think I have come off well.

There is, for instance, the case of a woman==I have known her for many a year—whom her mother conceived a dislike for at birth, at whom she did not nurse, as she had the other children, but left her a nursemaid and the bottle. The baby, however, preferred going hungry to being suckled through a rubber tube, and so grew more and more sickly, until the doctor roused the mother out of her antipathy. From being callous she now became most attentive to her child: a wet nurse was engaged and never an hour passed without the mother’s going to look after the baby. The youngster began to flourish and grew up a healthy woman. The mother made a pet of her and up to the time of her death, tried to win her daughter’s love, but in that daughter only hatred survived. Her whole life has been a steady chain of enmity whose separate links are forged by revenge. She plagued her mother so long as she lived, deserted her on her deathbed, persecuted, without realizing what she was doing, everyone who reminded her of her mother, and to[…]

[Right page]

[…]the end of her life will be a prey to the envy which hunger bred in her. She is childless. People who hate their mothers create no children for themselves, and that is so far true that one may postulate of a childless marriage, without further inquiry, that one of the two partners is a mother-hater. Whoever hates his mother, dreads to have a child of his own, for the life of man is ruled by the law, “As thou to me, so I to thee,’ yet this woman is consumed by the desire to bear a child. Her gait resembles that of a pregnant woman; when she sees a suckling babe her own breasts swell, and if her friends conceive, her abdomen also becomes enlarged. Though used to luxury and society, she went every day for years to help at a lying-in hospital, where she kept the babies clean, washed their swaddling clothes, and attended to the mothers, from whom in uncontrollable desire she would snatch the new-born infants to lay them to her empty breast. Yet she has twice married men of whom she knew in advance that they could beget no children. Her life is made up of hatred, anxiety, envy and the yearning cry of hunger for the unattainable.

There is also a second woman who went hungry for the first few days after her birth. She has never been able to bring herself to the point of confessing a hatred of her mother, who died young, but she is incessantly tormented by the feeling that she murdered her, though she recognizes this is irrational since her mother died during an operation of which the girl know nothing beforehand. For years she has sat in her room alone, living on her hatred for all mankind, seeing no one, spurning, hating.

To return to my own story: the nurse finally arrived and stayed in our home for three years. Have you ever pondered over the experiences of a baby who is fed by a wet nurse? The matter is somewhat complicated, at least if the child has a loving mother. On the one hand, there is that mother in whose body the baby has lain for nine months, care-free, warm in undisturbed enjoyment. Should he not love her? And on the other hand, there is that second woman to whose breast he is put every day, whose milk he drinks, whose fresh, warm skin he feels, and whose odor he inhales. Should he not love her? But to which of them shall he hold? The suckling nourished by a nurse is plunged into doubt, and never will he lose that sense of doubt. His capacity for faith is shaken at its foundation, and a choice between two possibilities for him is always more difficult than other people.[…]