By the end of the century, the first American medical schools were founded, quarantine hospitals were established to isolate and treat those with contagious diseases, and inoculation was known to be an effective treatment for smallpox. Yet the standard medical treatment of Washington’s era was not able to save him from his final illness, and some have suggested that bloodletting, purgatives, emetics, enemas, and blistering may even have hastened his death.

Having returned to Mount Vernon after John Adams was sworn in as the country’s second president, Washington spent much time outside, making the rounds of his estate. Washington endured five hours of rain, snow, hail, and high winds on Thursday, December 12, 1799, and didn’t change his wet clothes before dinner. The next day, Washington was outside in poor weather again, marking some trees for removal. That evening, unconcerned with his sore throat, he told Tobias Lear, his personal secretary, “You know I never take anything for a cold. Let it go as it came.”

“The debt of nature…must be paid by us all”

Above quote from a letter from George Washington to George Lewis, April 9, 1797

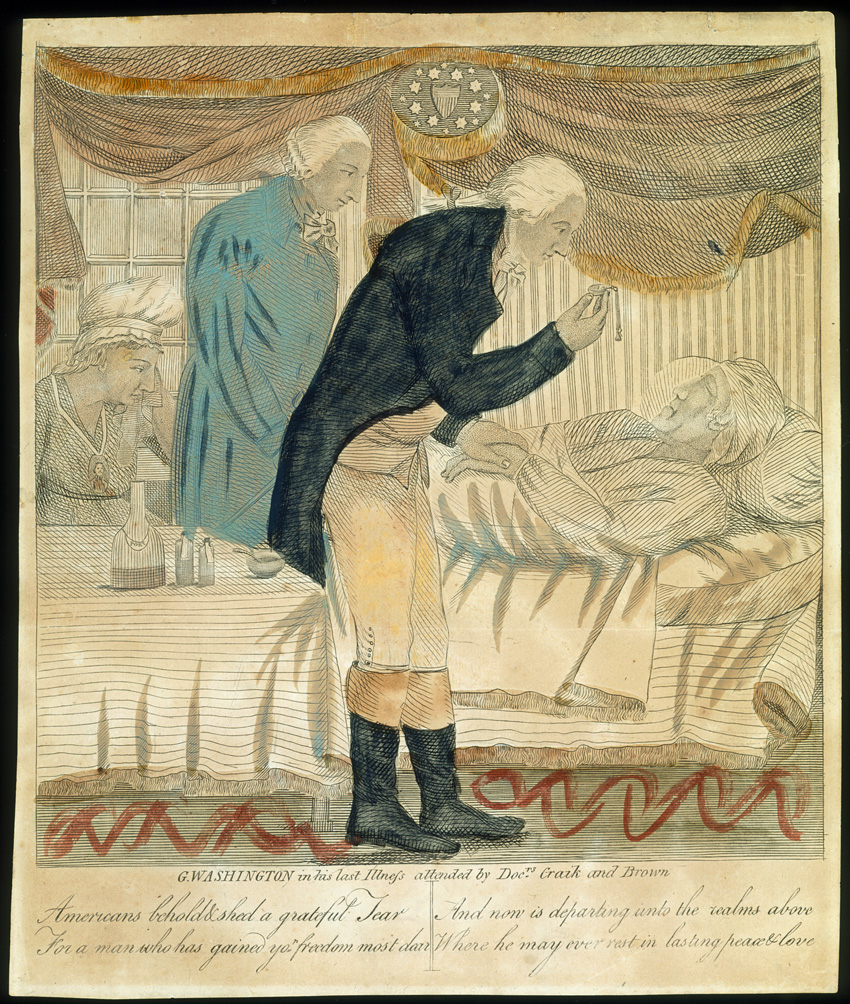

George Washington in His Last Illness attended by Docrs., early 19th century

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

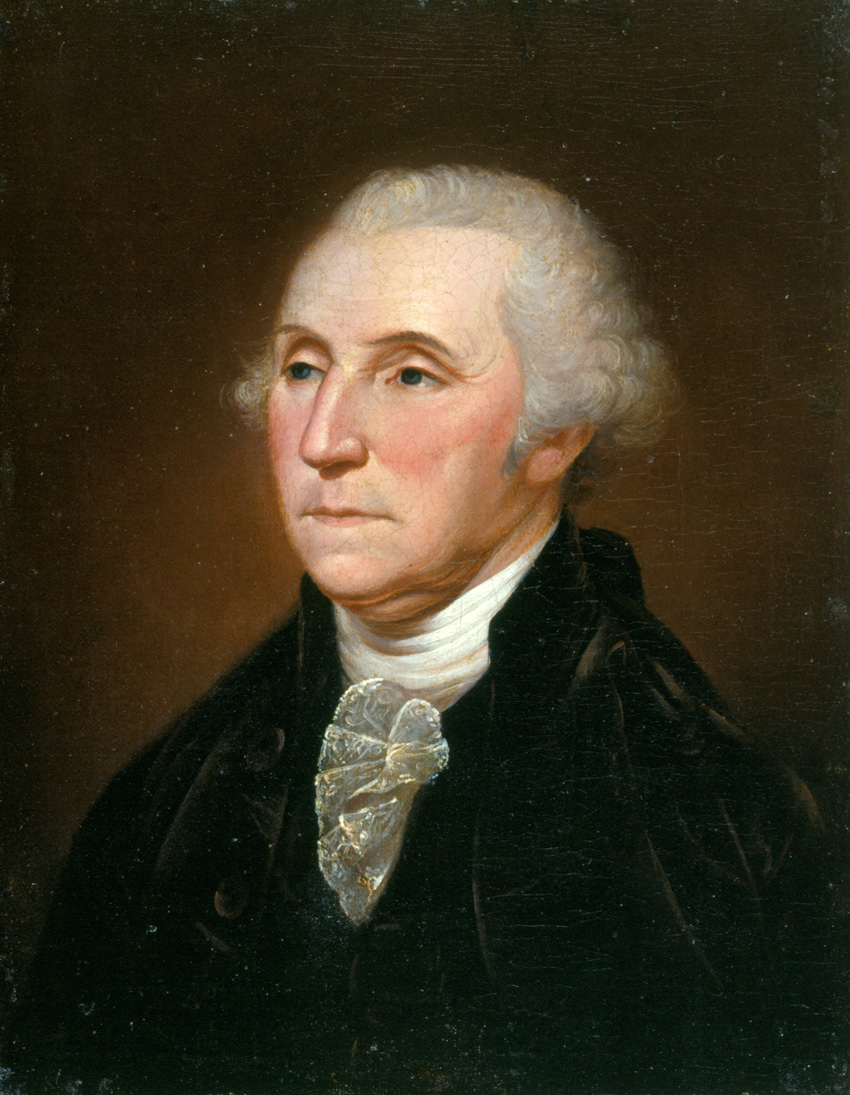

George Washington, Charles Willson Peale, 1795

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Late in life, George Washington sat for portrait artist Charles Willson Peale at Philosophical Hall in Philadelphia.

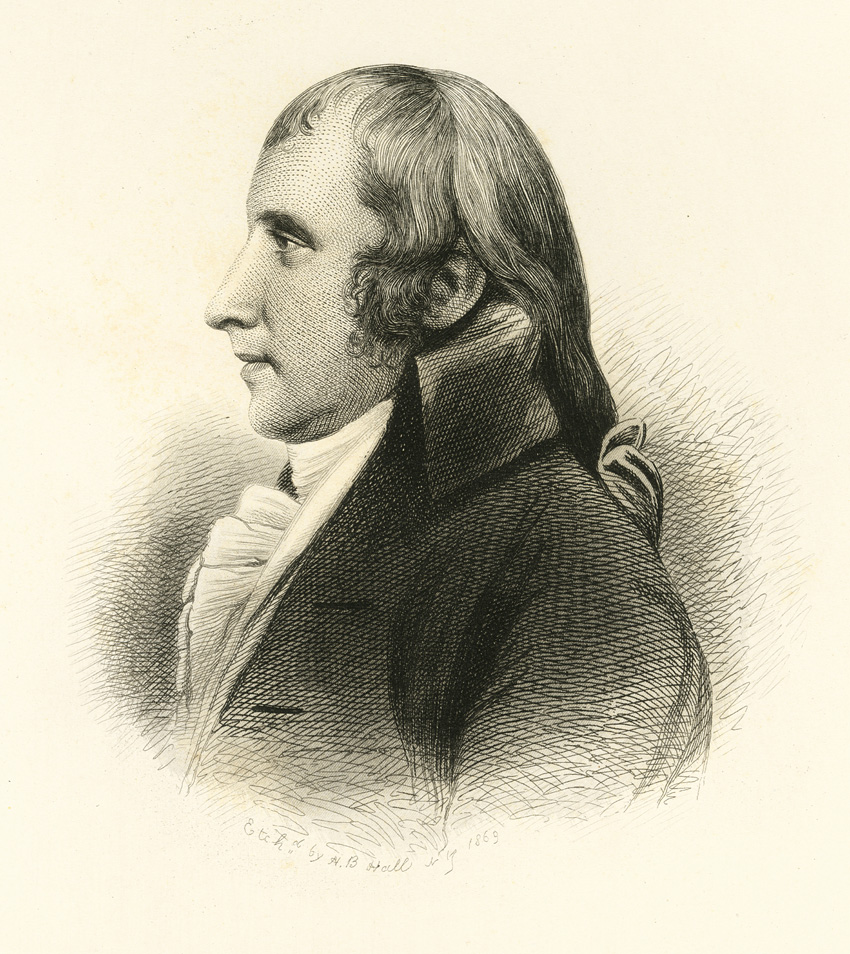

Tobias Lear, Washington’s personal secretary, Henry Bryan Hall, 1869

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Lear served as George Washington’s secretary from 1786 to 1799. His main duties included managing Washington’s personal correspondence and expense reports to Congress. Lear had a close relationship with the Washingtons, and was with the family when George died.

A page from Tobias Lear’s The last illness and Death of General Washington, December 14, 1799

Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Lear provided the most detailed description of the general’s last days. On Saturday, December 14, Washington awoke, feverish and with labored breathing. While he awaited the assistance of a physician, he tried home remedies. He instructed his overseer to bleed him and Lear applied a menthol vapor rub to his throat.

Breathing a Vein, James Gillray, 1804

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Phlebotomy or, bloodletting, was common in the 18th century. It was based on the belief that excessive blood, phlegm, and bile caused fever and inflammation. To balance the body’s humors, these fluids were purged using cutting tools, such as lancets and fleams, and the fluids were collected in bleeding bowls. Washington lost three quarts or half his blood volume during his final illness.

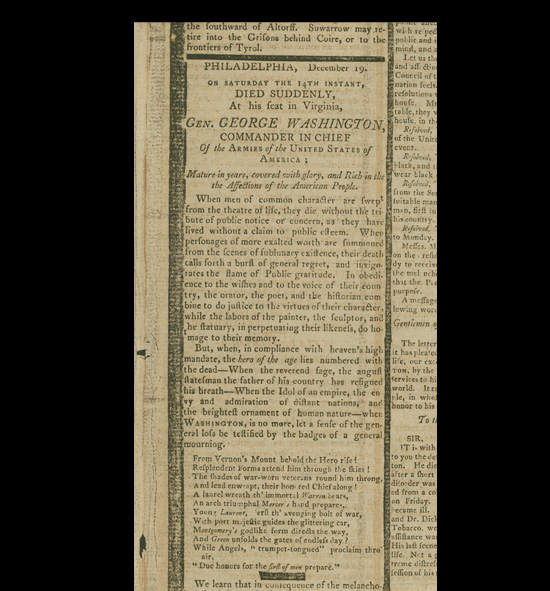

Newspaper notice of George Washington’s death, 1799

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Washington was attended by his close friend, Dr. James Craik, who perceived the gravity of the situation and enlisted the assistance of Dr. Gustavus Brown from Fort Tobacco, Maryland, and Dr. Elisha Dick, a young doctor from Alexandria, Virginia. While Dr. Dick opposed the excessive bleeding and proposed a tracheotomy, a new surgical procedure to relieve Washington’s labored breathing, he was overruled on both opinions by the senior doctors in attendance. He was bled four times in the last day of his life. Evidence suggests that Washington died from swelling and obstruction of his airway.

With the news of Washington’s death, the country went into mourning and hundreds of eulogies were delivered.

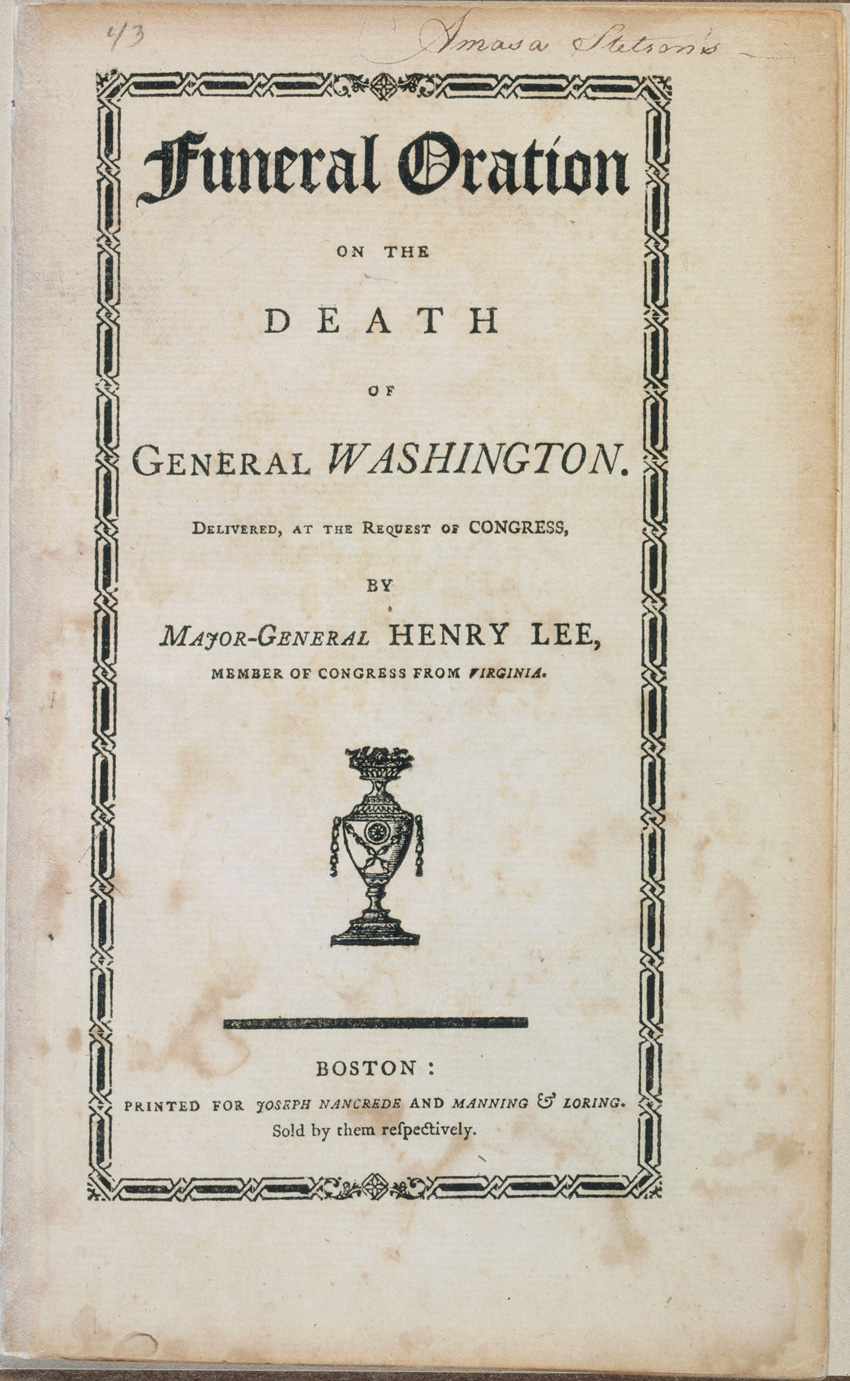

A funeral oration on the death of George Washington, Major-General Henry Lee, 1799

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Washington was attended by his close friend, Dr. James Craik, who perceived the gravity of the situation and enlisted the assistance of Dr. Gustavus Brown from Fort Tobacco, Maryland, and Dr. Elisha Dick, a young doctor from Alexandria, Virginia. While Dr. Dick opposed the excessive bleeding and proposed a tracheotomy, a new surgical procedure to relieve Washington’s labored breathing, he was overruled on both opinions by the senior doctors in attendance. He was bled four times in the last day of his life. Evidence suggests that Washington died from swelling and obstruction of his airway.

With the news of Washington’s death, the country went into mourning and hundreds of eulogies were delivered.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate, Carol Highsmith

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

![Page of handwritten notes [illegible].](img/gw-exhibition-journeysend-OB2113-lg.jpg )