tbd

Look for the leaf!

The willow leaf means this item was part of the original 1959 display.

The Origins of The Story of Aspirin

Acetylsalicylic Acid: The Story of Aspirin, notes to accompany an exhibit at the National Library of Medicine, Marie Harvin, 1959

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

For the National Library of Medicine (NLM), 1959 was a transformative year: the institution moved to a new building and adopted its current name. During this time, Marie Harvin, reference librarian, developed a display, Acetylsalicylic Acid: The Story of Aspirin. The materials she selected highlighted aspirin’s history from its ancient origins to the developments of the mid-20th century. Take Two and Call Me in the Morning revisits this earlier show as the NLM continues to evolve.

Chemists in Leeds University Laboratories, 1908

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

“The Willow,” A Curious Herbal: containing five hundred cuts...Volume 2, Elizabeth Blackwell, c. 1739

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Powdered Bark as Remedy

From ancient times, physicians and healers used willow bark to relieve pains, ease inflammation, and reduce fevers. After drying, they ground the bark in a mortar and pestle until the yellow, bitter tasting substance became a fine powder. A common dosage was about 20 grains of powder every four hours.

Herbarius (Herbalist), Arnaldus de Villanova, 1499

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Botanists call the white willow tree by its Latin name, “Salix alba.”

“An Account of the Success of the Bark of the Willow in the Cure of Agues…,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Edward Stone, 1763

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Reverend Edward Stone (1702–1768) is recognized as the first person to show willow bark’s effectiveness at relieving symptoms associated with ague and rheumatic fever. In 1763, he reported his discoveries to the Royal Society of London.

De medicinali materia, libri sex, Joanne Ruellio… (Of medicinal materials, book 6, Jean Ruel…), Dioscorides Pedanius of Anazarboz, 1550

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The earliest physicians of Western medical tradition showed willow tree bark’s medicinal properties. Hippocrates (c. 460–c. 370 BC) used the leaves to ease childbirth pains. Dioscorides (c. 40–c. 90 AD) treated colic, gout, and ear pains with the powder. Plinius (c. 23–79 AD) applied the bark as an analgesic, a pain reliever.

The English Physician; or, An Astrologo-Physical Discourse of the Vulgar Herbs of this Nation, Nicholas Culpeper, 1652

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

English botanist and physician Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) compiled information about hundreds of herbals and their medicinal value in his work The English Physician. Written for the layperson, he described the willow tree’s use for slowing bleeding wounds, reducing indigestion, improving urine flow, treating warts, and temporarily reducing the lust of men and women.

Nicholas Culpeper, MD, mid-1600s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

English botanist and physician Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) compiled information about hundreds of herbals and their medicinal value in his work The English Physician. Written for the layperson, he described the willow tree’s use for slowing bleeding wounds, reducing indigestion, improving urine flow, treating warts, and temporarily reducing the lust of men and women.

Modern Chemistry “Discovers” an Ancient Therapeutic

In the 1880s, modern chemistry fueled the pharmaceutical industry, using sophisticated experimental methods and technologies to work with organic compounds. German manufacturers took willow bark and synthesized an entirely new, complex drug that came to be known as “aspirin.” This new product effectively relieved pain and fever, lacked willow bark’s unpleasant taste, and had minimal reported side effects.

“Rapport sur un Mémoire de M. Leroux, pharmacien à Vitry-le-François …,” Annales de chimie et physique (“Report on a memoir of M. Leroux, pharmacist at Vitry-le- François…,” Annals of Chemistry and Physics), J. L. Gay-Lussac and François Magendie, 1830

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

In 1829, French chemist Henri Leroux isolated salicin, the active ingredient found in willow bark.

“Recherches sur les acides organiques anhydres,” Annales de chimie et de physique (“Research on anhydrous organic acids,” Annals of Chemistry and Physics), Charles Gerhardt, 1853

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The French chemist Charles Frédéric Gerhardt (1816–1856) was the first to identify salicylic acid’s chemical structure. He was also the first who synthesized acetylsalicylic acid, aiming to reduce the unpleasant gastric irritation of salicylic acid.

“Ueber die Constitution und Basictät der Salicylsäure,” Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (“On the constitution and basicity of salicylic acid,” Annals of Chemistry and Pharmacy), Hermann Kolbe and E. Lautemann, 1860

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

In 1860, Hermann Kolbe (1818–1884), a German scientist, created a method to synthesize salicylic acid, the building block of aspirin, from smaller molecules, instead of willow bark. Kolbe’s synthesis made the bulk industrial production of salicylic acid and aspirin possible.

“Sur de nouveaux produits extraits de la salicine,” Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des sciences (“On the new products extracted from salicin,” Weekly Reports of the Academy of Sciences), Raffaele Piria, 1838

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

In 1838, Italian chemist Raffaele Piria (1814-1865) isolated salicylic acid, an active derivative of the willow extract, salicin.

A Chemist’s Treasure

In the 1880s, German pharmaceutical company Friedrich Bayer & Co. became the industry leader when chemists developed a new substance, acetylsalicylic acid, which Bayer renamed “aspirin.” The new formulation was less irritating to the body and easier to absorb. In 1899, Bayer patented aspirin and its manufacturing processes and began shipping its product worldwide.

During World War I, the value of aspirin as a therapeutic increased for medical professionals and patients. Nurses dispensed aspirin in tablets to ailing military men, reducing aches and fevers and allowing the body to strengthen its natural defenses. Pharmaceutical companies developed formulas to lessen side effects, including allergic reactions and gastric bleeding.

“The Treatment of Acute Rheumatism by Salicin,” The Lancet, Thomas John MacLagan, 1876

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Scientists began testing aspirin’s effects on the body in the 1870s. Scottish physician Thomas MacLagan (1838–1903) published his findings in The Lancet after treating a patient for acute rheumatism using aspirin. He deemed the therapeutic a success despite the associated stomach irritation and bitter taste. German physicians Kurt Witthauer (1865–1911) and Julius Wohlgemuth (1874–1948) conducted additional tests in 1899, concluding that the healing powers of aspirin outweighed its side effects.

“ Aspirin, ein neues Salicylpraparat,” Therapeutische Monatsheft (“Aspirin, a new salicylic preparation,” Therapeutic Monthly Magazine), Kurt Witthauer, 1899

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Scientists began testing aspirin’s effects on the body in the 1870s. Scottish physician Thomas MacLagan (1838–1903) published his findings in The Lancet after treating a patient for acute rheumatism using aspirin. He deemed the therapeutic a success despite the associated stomach irritation and bitter taste. German physicians Kurt Witthauer (1865–1911) and Julius Wohlgemuth (1874–1948) conducted additional tests in 1899, concluding that the healing powers of aspirin outweighed its side effects.

“Ueber Aspirin [Acetylsalicylsaure],” Therapeutische Monatsheft (“About Aspirin [Acetylsalicylic acid], Therapeutic Monthly Magazine), Julius Wohlgemuth, 1899

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Scientists began testing aspirin’s effects on the body in the 1870s. Scottish physician Thomas MacLagan (1838–1903) published his findings in The Lancet after treating a patient for acute rheumatism using aspirin. He deemed the therapeutic a success despite the associated stomach irritation and bitter taste. German physicians Kurt Witthauer (1865–1911) and Julius Wohlgemuth (1874–1948) conducted additional tests in 1899, concluding that the healing powers of aspirin outweighed its side effects.

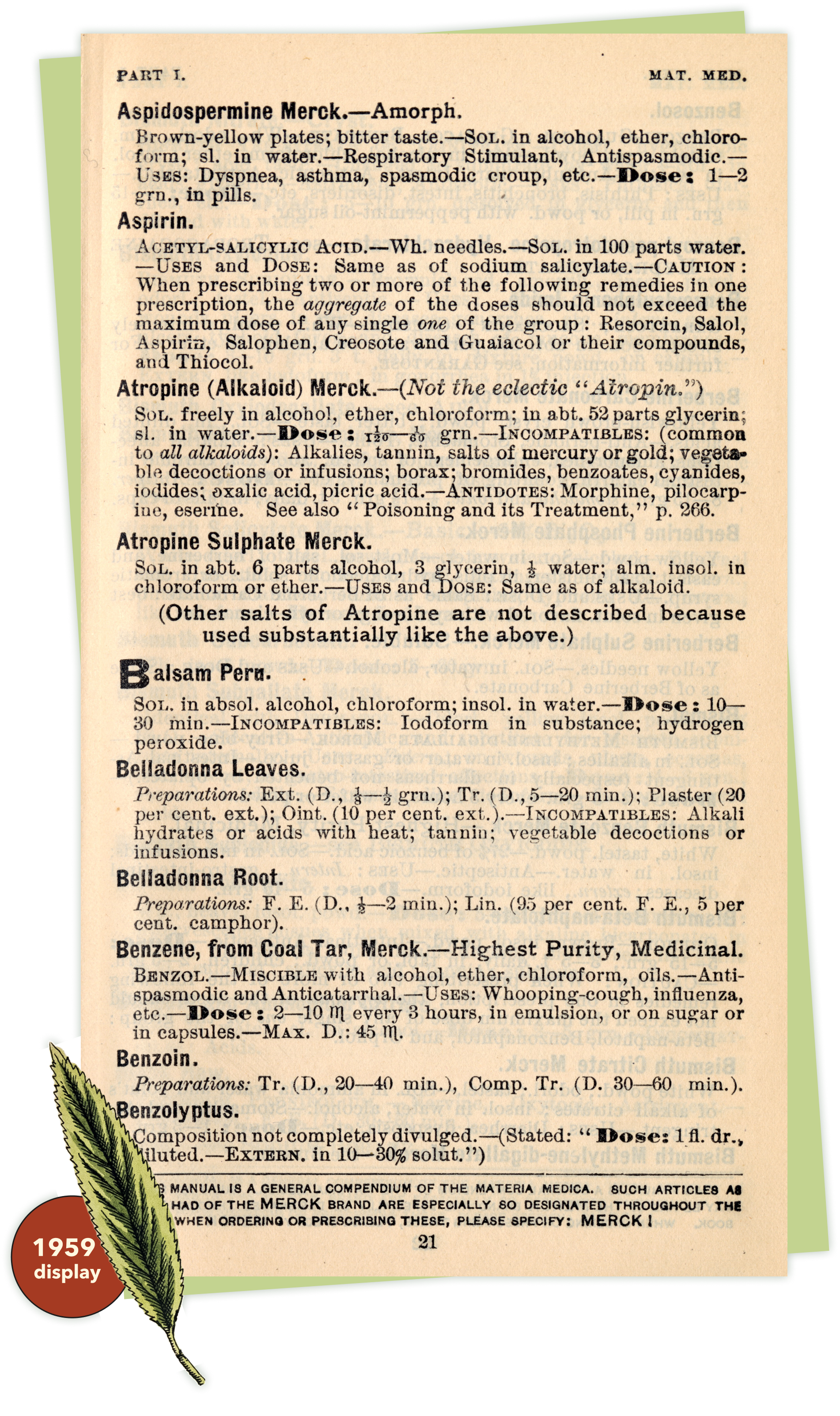

Merck’s 1901 Manual of the Materia Medica: a read-reference pocket book for the practicing physician and surgeon, Merck & Co., 1901

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

As part of their marketing and education efforts, pharmaceutical companies issued annual reference pocket guides for physicians and pharmacists. These guides consisted of prescription formulas and descriptions of various therapeutics’ applications.

Dr. Miles’ Aspir-Mint: a pleasant, effective, modern formula, Dr. Miles Medical Co., c. early 1900s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Dr. Miles Medical Company, an American patent medicine firm, advertised flavored aspirin and shipped free samples to physicians and pharmacists. Aspir-Mint’s palatable taste encouraged more patients to take it.

Hospital Heroes, Elizabeth Walker Black, 1919

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

American nurse Elizabeth Walker Black wrote of providing care to military men during World War I. She described how nurses dispensed aspirin for headaches following operations and shared medicine between hospital units.

Advertisement from Laboratoire des Produits Usines du Rhône, c. early 1900s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The French pharmaceutical company Usines du Rhône produced advertisements to promote their aspirin product. The ads used the visual trope of the hospital nurse to assure customers of aspirin’s effectiveness.

Postcard from Laboratoire des Produits Usines du Rhône, c. early 1900s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The French pharmaceutical company Usines du Rhône produced advertisements to promote their aspirin product. The ads used the visual trope of the hospital nurse to assure customers of aspirin’s effectiveness.

Advertisement from Laboratoire des Produits Usines du Rhône, c. early 1900s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The French pharmaceutical company Usines du Rhône produced advertisements to promote their aspirin product. The ads used the visual trope of the hospital nurse to assure customers of aspirin’s effectiveness.

Medical Nursing, Arthur Stanley Woodwark, 1914

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

British physician A. S. Woodwark (1875–1945) published this nursing textbook outlining symptoms and related therapeutics, including aspirin.

Global Needs Create Global Markets

The influenza pandemic of 1918 created an urgent, worldwide demand for treatments and remedies. The flu revolutionized what scientists knew about infectious diseases and how they developed medicines. Pharmaceutical companies responded by doubling their manufacture and distribution of aspirin and aspirin-based products.

Influenza in Alaska and Porto Rico: hearings before Subcommittee of House Committee on Appropriation in Charge of Relief in Alaska and Porto Rico, U.S. Congress, 1919

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

During the influenza pandemic, public officials testified before Congress that the disease created a crisis in their territories as death rates rose into the thousands. They requested “epidemic relief”—additional funds—for food, transportation, and medical supplies and personnel.

A U.S. Army field hospital influenza ward in Hollerich Luxembourg, c. early 1900s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Influenza arrived at army camps in waves in 1918 and 1919. Cramped conditions in the barracks helped spread the virus. Medical staff hung sheets between cots to protect each man from another’s breathing.

A U.S. Army field hospital influenza ward in Aix-les-Bains, France, c. early 1900s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Influenza arrived at army camps in waves in 1918 and 1919. Cramped conditions in the barracks helped spread the virus. Medical staff hung sheets between cots to protect each man from another’s breathing.

Pharmaceutical advertisement of injectable aspirin, c. 1900s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

During the influenza pandemic, people in China died in large numbers. China Pharmaceutical Company, based in Guangzhou, China, purchased and distributed the powdered form of aspirin. A physician mixed the powder with a liquid solution to inject the therapeutic into patients to relieve muscle and joint pains and headaches.

Pharmaceutical advertisement of aspirin tablets, c. 1935

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

In China, a pharmaceutical company distributed Bayer aspirin tablets. Here, an advertisement for Bayer, with its well-known logo stamped on the drug in Chinese characters, informed medical officials that aspirin gave relief to head- and toothaches, fevers, and arthritis.

Scientists Revisit Aspirin’s Potential

In the latter half of the 20th century, scientists began examining aspirin for benefits beyond pain relief and fever reduction. Concurrently, doctors observed side effects with increased consumption of the drug. Both the promise and the potential dangers of aspirin prompted clinical research.

John R. Vane, 1977

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

British pharmacologist John Robert Vane (1927–2004) and Swedish biochemists Sune K. Bergström (1916–2004) and Bengt I. Samuelsson (1934–) shared the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their breakthroughs in research on prostaglandins, hormone-like compounds in the body that aspirin inhibits to prevent blood clots.

Bengt Samuelsson, c. 1980s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

British pharmacologist John Robert Vane (1927–2004) and Swedish biochemists Sune K. Bergström (1916–2004) and Bengt I. Samuelsson (1934–) shared the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their breakthroughs in research on prostaglandins, hormone-like compounds in the body that aspirin inhibits to prevent blood clots.

Sune K. Bergström (right) with (from left to right) Mary Lasker, Michael DeBakey, and Congressman John Brademas, c. 1960s

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

British pharmacologist John Robert Vane (1927–2004) and Swedish biochemists Sune K. Bergström (1916–2004) and Bengt I. Samuelsson (1934–) shared the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their breakthroughs in research on prostaglandins, hormone-like compounds in the body that aspirin inhibits to prevent blood clots.

“Long-Term Results in Early Cases of Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Either Cortisone or Aspirin,” British Medical Journal, Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation on Clinical Trials of Cortisone, April 13, 1957

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Researchers led clinical studies to learn more about aspirin’s therapeutic capabilities compared to other drugs in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. In this multi-year study, scientists observed few differences in the short term. However, over a longer period, more patients reported that aspirin was the preferred therapy.

Aspirin, Platelets, and Stroke: Background for a Clinical Trial, William S. Fields, MD and William K. Hass, MD, 1970

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

By the 1970s, scientists’ studies had shed light on aspirin’s role as an anti-inflammatory agent and preventive therapeutic. This symposium discussed prescribing baby aspirin as an antiplatelet in stroke prevention.

Aspirin in Modern Therapy: A Review, Maurice L. Tainter, MD and Alice J. Ferric, MD, 1969

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Published by Bayer Co., physicians reviewed existing scientific literature to demonstrate aspirin’s value as a therapeutic.