Embryology

Identical twins develop when a single fertilized egg, also known as a monozygote, splits during the first two weeks of conception. Conjoined twins form when this split occurs after the first two weeks of conception. The monozygote does not fully separate, and eventually develops into a conjoined fetus that shares one placenta, one amniotic sac, and one chorionic sac. Because the twins develop from a single egg, they will also be the same sex. The extent of separation and the stage at which it occurs determine the type of conjoined twin, i.e., where and how the twins will be joined.

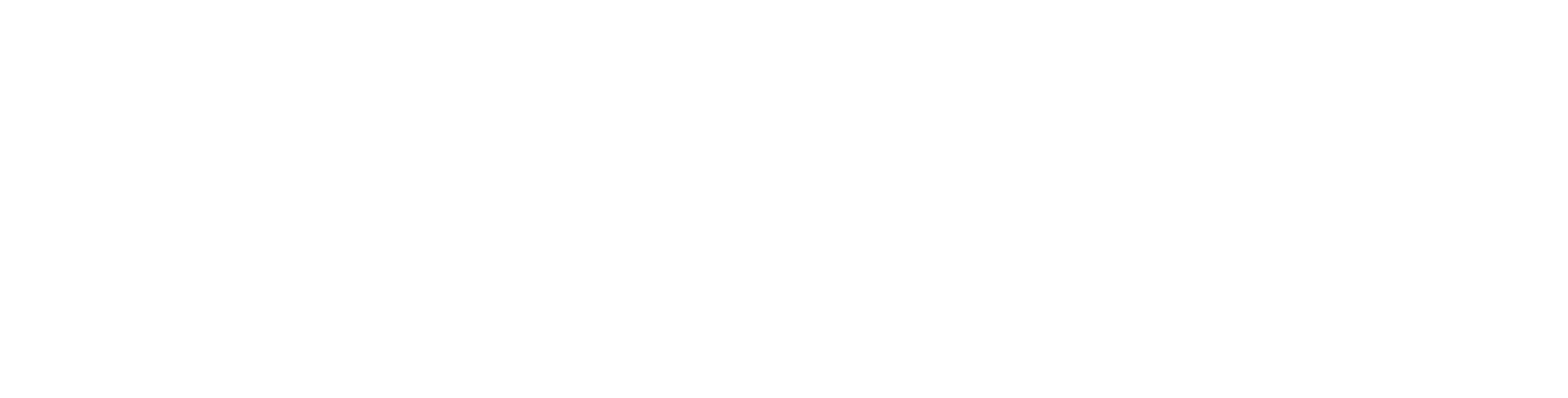

The diagram at below illustrates the germ layers in embryos of conjoined twins. The proximity of the segments determines how much shared tissue there will be. The further apart the segments, the greater the likelihood that the organs will develop fully in each fetus. If the segments are at their farthest point, there will only be a minimum of tissue and cartilage joining the twins, i.e. omphalopagus twins will develop.

Classification

Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hillaire was the first teratologist to classify conjoined twins, using Greek etymology to describe the twins in terms of their shared anatomy. Many of his terms are still in use today. Commonly occurring types of conjoined twins include craniopagus: joined at the cranium (head); thoracopagus: joined at the thoracic cavity (chest); omphalopagus or xiphopagus: joined in the region of the umbilicus; ischiopagus: joined at the inferior margins of the coccyx and sacrum, with two separate spinal columns; and pygopagus: joined at the lateral and posterior surfaces of the coccyx and sacrum.

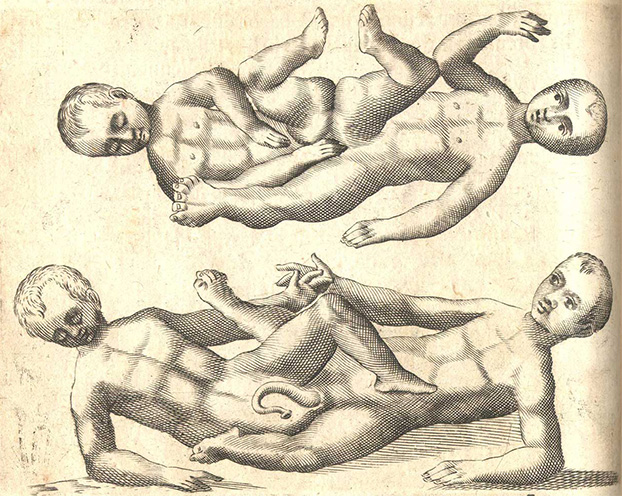

Age of Superstition

From medieval times through the Enlightenment, conjoined twins were viewed as monsters. Their existence simultaneously horrified and amazed the common person. The established medical explanation of the day, from Hippocrates, reasoned that a conjoined twin was simply the result of there being too much seed available at conception for just one child, but not enough for two distinct beings. Even so, popular theories fueled the public's fear and wonder by suggesting that conjoined twins were the result of impure conception or the witnessing of some evil or traumatic event during pregnancy.

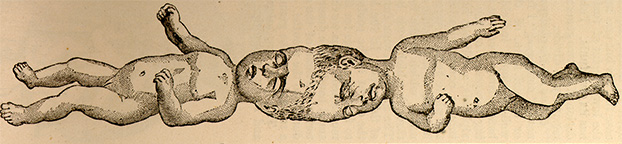

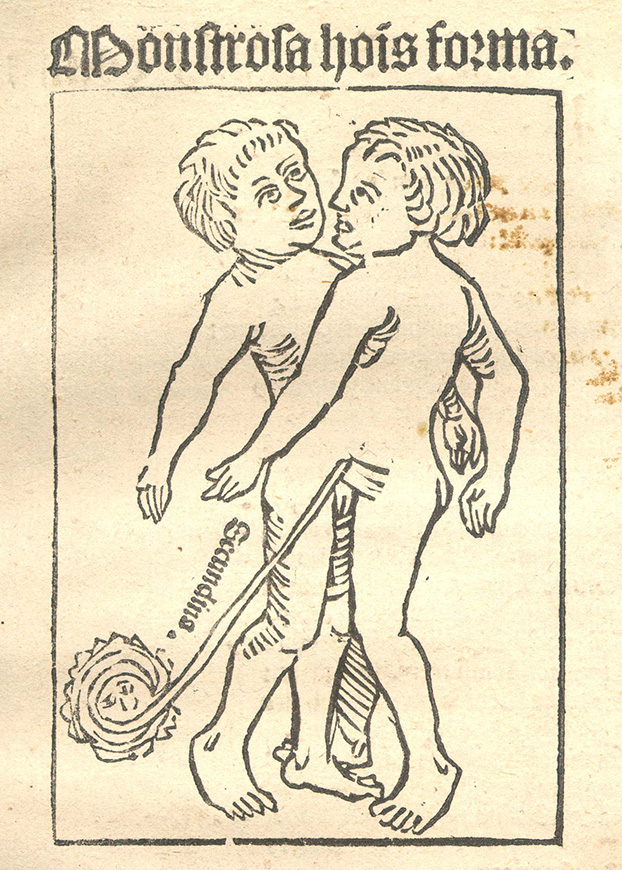

Books depicting all sorts of monsters, both real and imagined, were extremely popular among the literate during this period. The authors often copied extensively from each other, bringing long-told tales with new illustrations to another generation. Images of conjoined twins from some of the more popular works by Jacob Locher, Fortunio Liceti, the respected surgeon Ambroise Paré, and the anonymous author of Aristotle's Compleat Masterpiece are displayed below.

Marvels on Exhibit

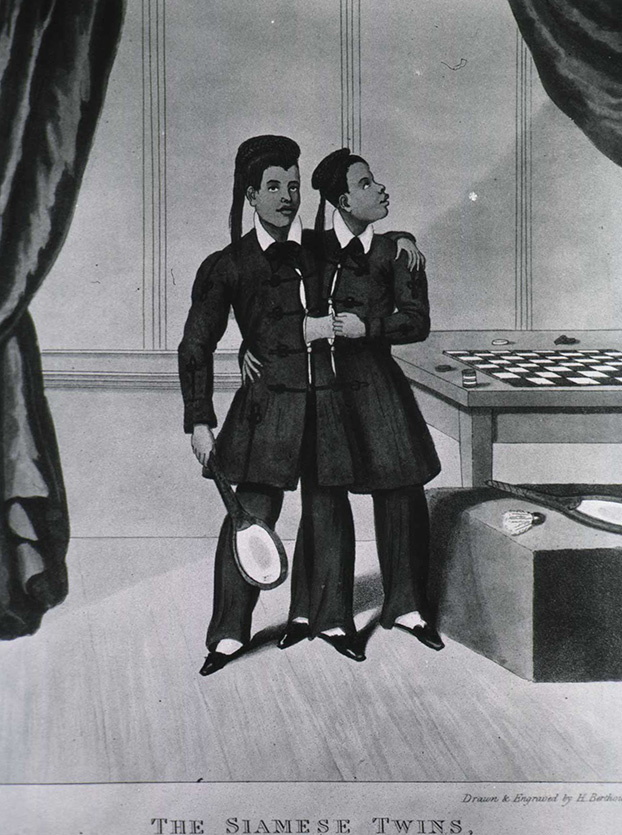

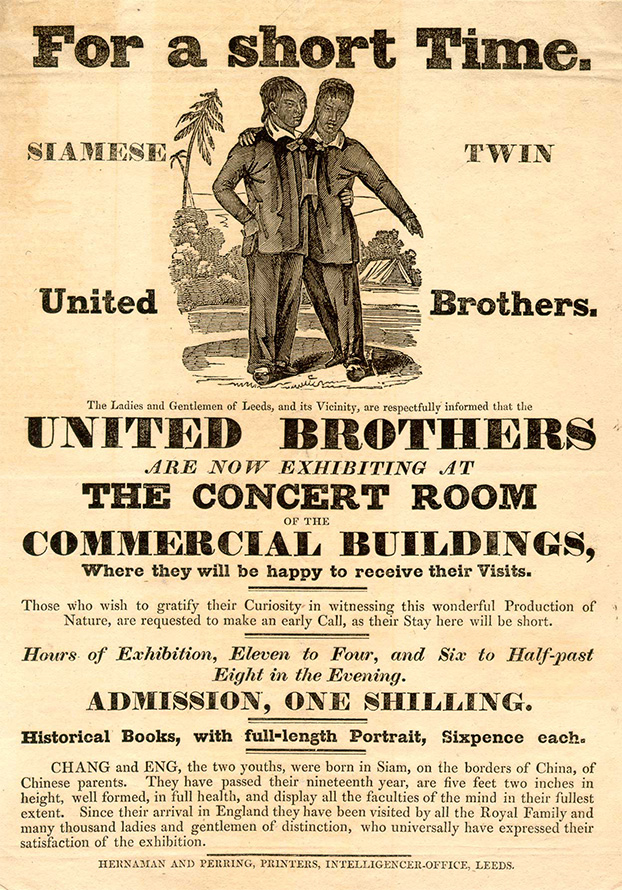

Chang-Eng Bunker

Chang-Eng Bunker were born on May 11, 1811 to Chinese parents in Siam (Thailand). At the time, their birth was viewed as a portent of disaster. The Siamese king Rama II initially ordered them put to death, before becoming convinced that the twins themselves were harmless. By their teens, the twins had found favor with King Rama III, who showered them with gifts and even sent them on diplomatic missions. A British merchant, Robert Hunter, and American sea captain, Abel Coffin, convinced Rama III to allow the twins to go on a two- and one-half-year exhibition tour in America and England from 1829 to 1831. Shortly after this tour, Chang-Eng took control of their career and earned a living as entertainers for the next four decades.

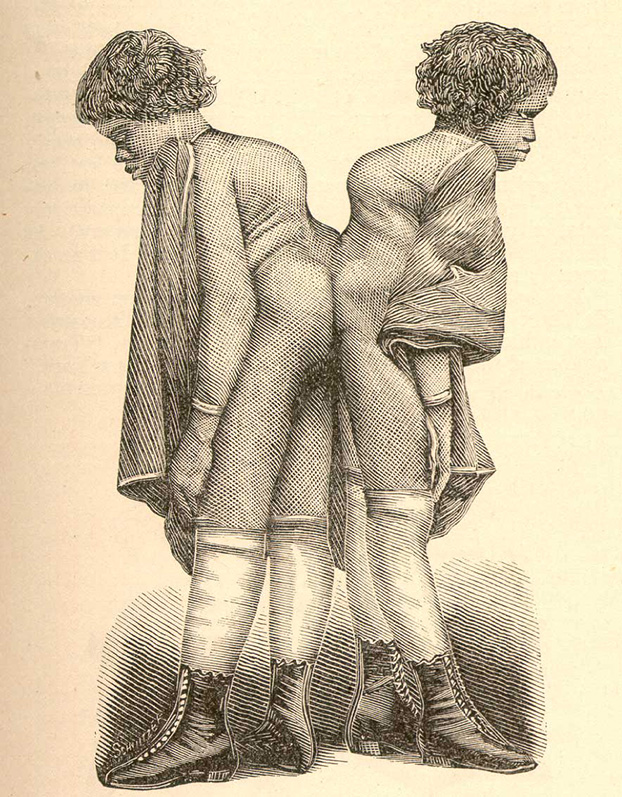

Touring the world, their stage presence and their uniqueness made them famous in very little time. Many marveled at the thick, fleshy ligament, five to six inches long and eight inches in circumference, that connected them at the base of the chest. Despite the prevailing societal idea that conjoined twins were monstrous, inhuman beings, Chang-Eng became accepted and respected by society, and were often received by royalty.

At age 28 Chang-Eng settled down to be farmers in North Carolina, where they married the Yates sisters in 1843 and maintained separate households. The couple produced 21 children between the two families, though only 11 survived to maturity. Financial necessity compelled Chang-Eng to return to show business and make paid public appearances. In their later years, they often appeared with their children, which both piqued audience curiosity and demonstrated their humanity. On their return voyage from Russia in 1870, Chang became paralyzed from a stroke, which required Eng to support him physically for the remaining three years of their lives. Chang-Eng died on January 17, 1874, at the age of 62.

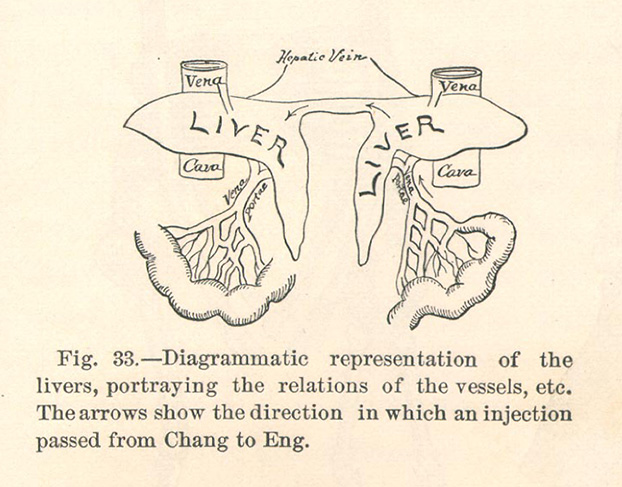

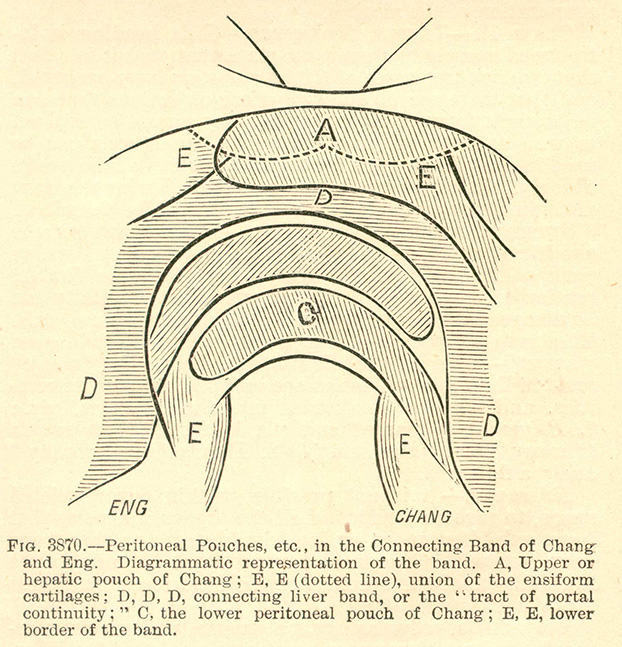

Autopsy Report on Chang-Eng

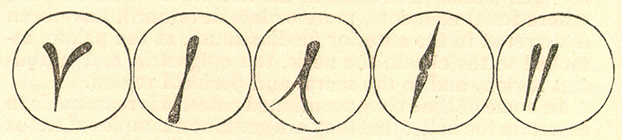

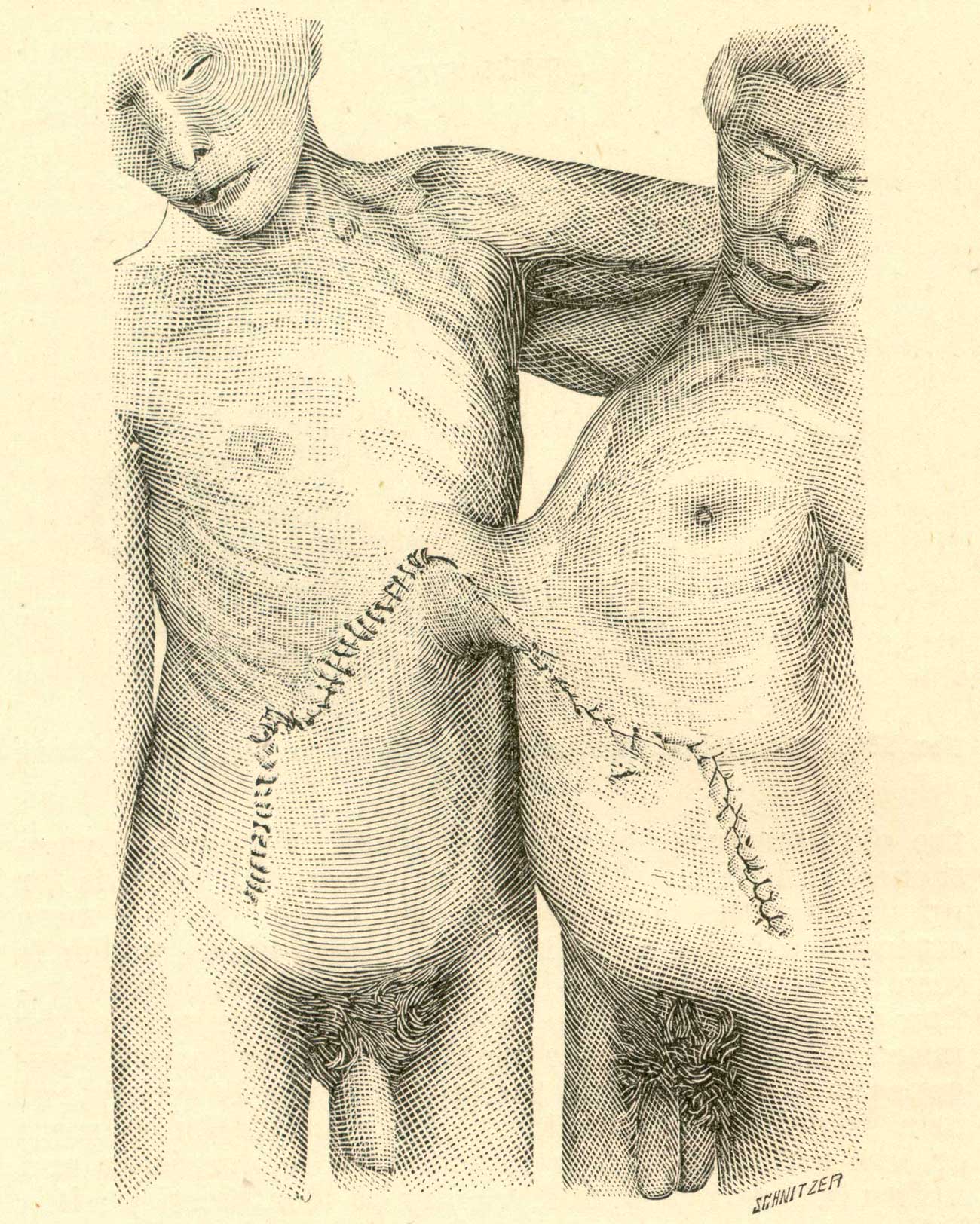

With the widows' permission, a detailed autopsy of Chang-Eng was conducted by Drs. William Pancoast and Harrison Allen in the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia from February 10-11, 1874. Shown below from the autopsy report are a contemporary sketch of the bodies and a diagram illustrating the conjoined tissues and hepatic vessels of the connecting band. Given the shared hepatic vessels, it is doubtful that a skilled 19th-century physician could have successfully separated the twins without causing the death of one twin.

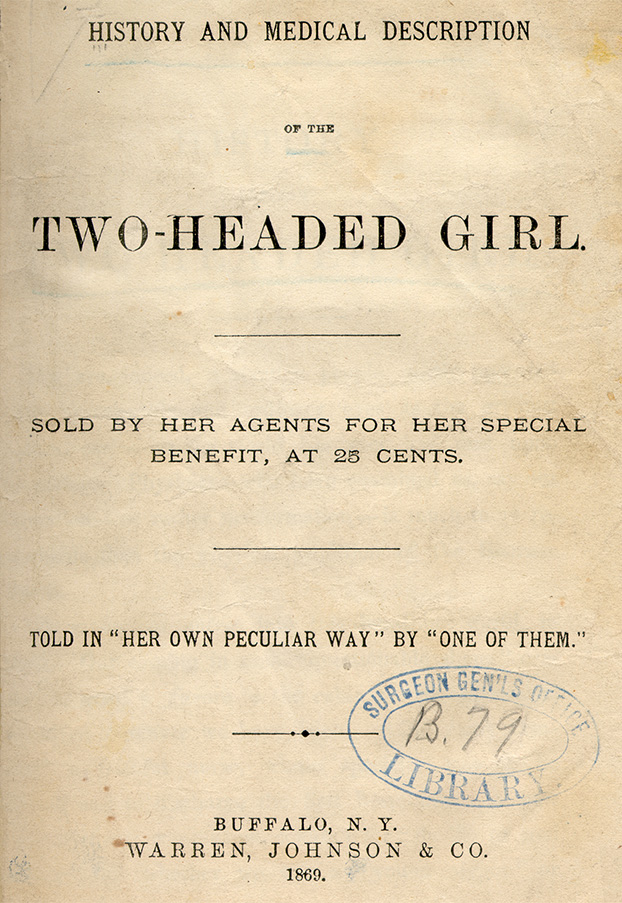

Millie-Christine McCoy, were born in Columbus County, North Carolina, on July 11, 1851 as ordinary slaves. Both girls were remarkably healthy although Millie would always remain slightly smaller. Between the ages of 10 months and 6 years of age, the twins were sold at least three times (legally and illegally) and exhibited throughout the United States and England. Millie-Christine were frequently examined by physicians in the towns where they appeared to confirm that they were conjoined. The physicians were astonished to find a pair of conjoined twins of African American descent. They were described as interesting, intelligent people who had nothing of monstrosity in their appearance.

North Carolina merchant Joseph Pearson Smith purchased Millie-Christine's parents and family from the McCoys and his wife taught them how to read and write and sing and dance. They became fluent in five languages and were accomplished pianists, singers, and dancers who toured the world. They were frequently billed as "The Two-Headed Nightingale" after their beautiful singing voices. In 1869, the twins issued their autobiography, "History and Medical Description of the Two-Headed Girl," which was purchasable for $.25 at their public appearances.

After a successful thirty-plus year career, the sisters stopped performing in shows and retired to their home in North Carolina. In 1909, a fire destroyed all their possessions and they suffered great financial loss. The twins' health also began to decline. Millie contracted tuberculosis, which later affected Christine, and eventually claimed both their lives on October 8, 1912.

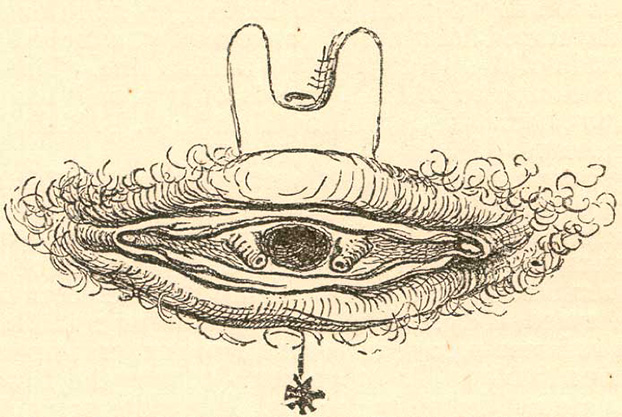

Physical Examination of Millie-Christine

In 1871, while touring in Philadelphia with Chang-Eng Bunker, Millie-Christine were sent to Dr. William Pancoast to be treated for an anal fistula. He published details of his examination, including photographs and sketches of their conjoined tissues, in the Photographic Review of Medicine and Surgery. His examination confirmed what other physicians had already determined: Millie-Christine shared one vulva and one anus but had separate urethras and bladders; the labia majora, although connected to two clitorises, ran continuous across the vulva and protected but one vagina and one uterus. He characterized the band of their union as containing mostly cartilage with shared osseous tissue at the sacrum.

Separation Surgeries

Brief Overview of Attempts and Successes

Historically, the separation of conjoined twins was frowned upon. Even if the physicians thought it might be anatomically possible, the twins' relations, who often had a vested financial interest in keeping the twins together, usually dismissed the idea. In fact, surgical separation was only seriously considered if one of the twins acquired an incurable disease. For example, both Eng and Millie were advised to seriously consider separation when Chang and Christine became gravely ill with pneumonia and tuberculosis, respectively; both refused.

Early surgeries were usually only performed on xiphopagus twins, which were joined by only a band of skin and tissue. The earliest recorded successful case occurred in 1690, when two sisters were separated by means of having a ligature around the band tightened daily until at last the final bit of skin was separated by a knife.

Surgeries on other types of twins, with more shared tissues or organs, frequently resulted in the survival of only one twin. Such was the case of Maria-Rosalina, thoracopagus twins who were separated in May 1900 by Eduoard Chapot-Prévost. Maria died eight days after separation, but Rosalina survived.

By the 1950s, advancing medical knowledge and technology enabled both conjoined twins of many different types to survive separation. Dr. Maitland Baldwin performed one of the first successful operations to separate craniopagus twins, on Dec. 11, 1956, at the National Institutes of Health. On Oct. 5, 1957, at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Dr. C. Everett Koop performed one of the first successful operations to separate pygopagus twins. Nearly twenty years later, Koop also led a team at Children's Hospital that successfully separated ischiopagus twins, Clara and Alta Rodriguez, who are profiled below.

Clara-Alta Rodriguez

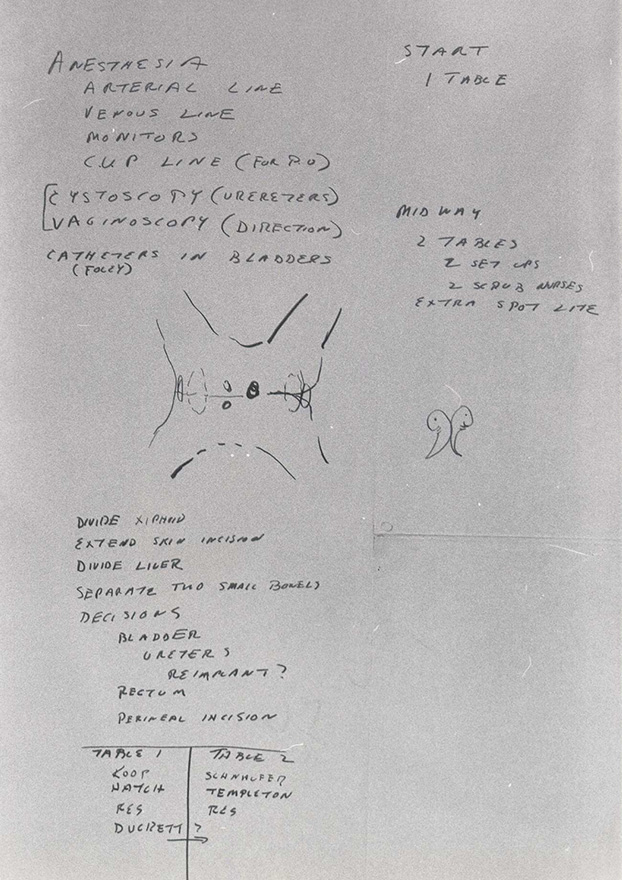

Clara and Altagracia (Alta) Rodriguez were born in San José de Ochoa, Dominican Republic, on August 12, 1973. They were ischiopagus twins, joined together at the lower trunk and pelvis. Their gastrointestinal urinary and reproductive systems were partially united. Clara was the dominant twin of the two; Alta was clearly much weaker.

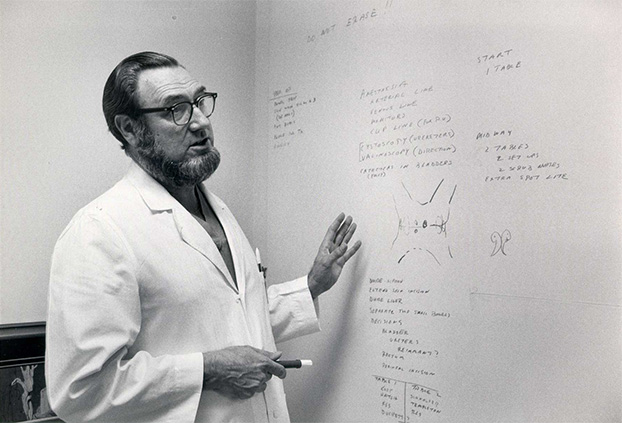

Thanks to the efforts of relatives and church groups in the United States, the one-year old twins were brought to The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia to be separated in September 1974. Chief of Pediatric Surgery Dr. C. Everett Koop, who had successfully performed a similar surgery 18 years earlier, said that if they remained conjoined, the girls would never be able to sit up at the same time.

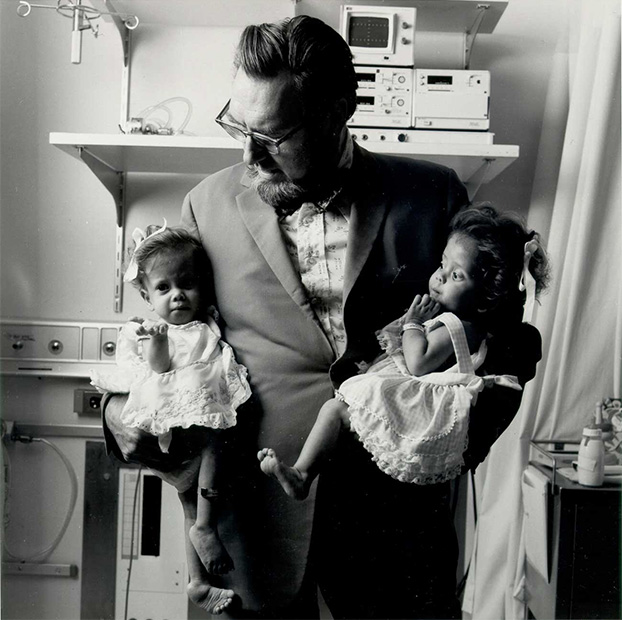

Koop led a team of 26 doctors and nurses in the eight-hour separation surgery. Post-operatively, the girls remained in the intensive care unit for 82 days. Additional surgery was also required to shape the girls' pelvic bones so that they would be able to walk.

The twins returned home in 1975, where Dominican President Joaquin Balaguer awarded Dr. Koop with a medal for the surgery. Mrs. Rodriguez was honored with a presidential decree which allowed her to travel to Puerto Rico to obtain baby supplies and medicine not available in her own country, and to bring them back duty-free. Sadly, one year after the separation of the two sisters, Alta choked on a bean. Clara survived to maturity and gave birth to a healthy baby boy in 1994.

Credits

This site was curated in 2006 by Laura Hartman, Rare Book Cataloguer, History of Medicine Division, with much assistance from student intern Kelly S. Clark, a Wilson High School senior working in HMD as part of NLM's Adopt-A-School Internship Program.

This site was designed by Astriata, LLC.

You can view the original website, including the full credits for the project, archived in the NLM Institutional Archives web collection.

Note: All images displayed in the separation surgeries section may be found in the C. Everett Koop Papers at the National Library of Medicine and are the courtesy of Dr. Koop. Images of the separated twins taken at the hospital are posted to the website by permission of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Every effort was made to secure the permissions to post the other images, but the current copyright owner either could not be identified or could not be contacted. If you have information regarding the copyright owner, please contact us at NLM Customer Support.

Bibliography of Conjoined Twins

Bibliography of Conjoined Twins

A Cinematic and Physiological Puzzle: Soviet Conjoined Twins Research, Scientific Cinema and Pavlovian Physiology by Nikolai Krementsov, PhD, (University of Toronto)

A Cinematic and Physiological Puzzle: Soviet Conjoined Twins Research, Scientific Cinema and Pavlovian Physiology by Nikolai Krementsov, PhD, (University of Toronto)

The C. Everett Koop Papers: Congenital Birth Defects and the Medical Rights of Children: The "Baby Doe" Controversy

The C. Everett Koop Papers: Congenital Birth Defects and the Medical Rights of Children: The "Baby Doe" Controversy